(Picture courtesy of ke7.org.uk)

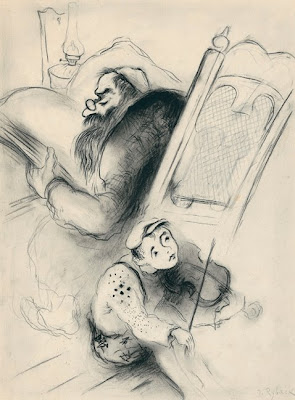

Eliyahu is also the harbinger of the Moshiach, which is why we are accustomed to speak of Eliyahu on Motza’ei Shabbos; for Chazal taught us that the Moshiach will not arrive on Erev Shabbos, but he may arrive immediately upon the termination of the holy day. Here are two first-hand Eliyahu ha-Novi stories – well, at least, they might be – which we can tell while the nights are not too short and it is still “Melaveh Malkah Season.”Elijah Comes For ShaloshudesOne Shabbos in the summer of 1980, as the sun disappeared behind the trees, a group of middle-aged and elderly Jews sat with the Rabbi of our little Orthodox shul in Connecticut to partake of "shaloshudes," the third Shabbos meal. I was the only person there under thirty (although by only a year). As the Rabbi began to sing “Askinu se’udasa,” we heard a commotion in the hall nearby. I went to the door to see what was going on, and observed the elderly Mrs. Goldstein (name changed to protect the record), one of the five star generals of the synagogue's corps of volunteers, remonstrating with a tramp who had came to the shul asking for food. The stooped, ragged man looked like he might have walked out of a John Steinbeck novel: a real old-time hobo.

"Go away!" the diminutive but fierce Protector of the Kitchen commanded. "Don't your own people have food for you? This is a synagogue! Go to the church instead!"

The shabby old man turned and shuffled away, and I returned to the table, deeply troubled, as the Rabbi continued to sing the melodies of shaloshudes with those gathered around him.

"Look at all of this food," I interrupted. "Couldn't we spare something for a hungry old man?" I had hitch-hiked around the country a few times during my teenage years, and knew what it feels like to be hungry and without a roof over your head.

"Don't worry," the Rabbi assured me, "he won't starve."

"Maybe he's Eliyahu ha-Novi,” I suggested. "Doesn't he often come looking like a ragged beggar? Maybe we just turned away Eliyahu ha-Novi without a crust of bread!"

The Rabbi flinched. Without delay, he poured a cup of wine and made ready to recite the Grace After Meals. "OK, Dovid," he whispered, "we'll go find him in a few minutes, right after Ma'ariv."

So we hastily recited the Grace After Meals, reassembled in the basement minyan room for Ma'ariv, and ten minutes later hastened to the Rabbi's station wagon in search of our mysterious visitor. We drove through all the side streets in the neighborhood until we reached Case Street, near the old City Hall building, where we spied an old man who might have been the same wandering tramp -- although not necessarily -- walking down the hill. However, when we asked if he had come to the synagogue in need of food a little while ago, he snarled at us like a growling dog, and told us to leave him alone.

The old beggar was nowhere to be found. If indeed Eliyahu ha-Novi had come to our shul for herring and crackers, he seemed to have disappeared as mysteriously as he had come. I wouldn’t see him again for nearly a decade.

Our First Visit to BreslovIn Elul of 1988, still before glasnost and the rebirth of the Uman Rosh Hashanah gathering, my family and I were part of a small group that visited Reb Nachman's grave site, as well as other kivrei tzaddikim in the Ukraine. Then we continued onward to Eretz Yisrael to spend Rosh Hashanah in Meron. The trip was action-packed, and would require many pages to describe. However, one memorable incident took place in the village of Breslov.

Our Intourist bus arrived just before sundown (note: the same time of day as in the previous story) and parked at the foot of a steep hill, atop which was the old Jewish cemetery where Reb Noson, Reb Aharon the Rov, and other Breslever Chassidim were buried. A light rain was falling, so some of us donned umbrellas and rain coats, Rabbi Symcha Bergman being particularly well prepared; others (like me) had packed their rain gear in their suitcases and therefore left the bus defenseless against the elements. Rabbi Shlomo Goldman had fallen ill and was feverish, so he stayed behind; knowing the resolute Reb Shlomo a little better now, I realize in retrospect that he must have been in pretty bad shape not to go. I asked my wife Shira to stay in the bus and keep warm and dry, and headed up the steep muddy path. The Ukrainian blotteh (muck) proved to be as slippery as ice, and after falling once, I climbed up the grassy shoulder of the deeply rutted dirt road and slowly made my way past several decrepit farms, one of which housed two Volvos in a covered cattle stall made of planks. Finally we came to the crest of the hill and the stone steps marking what had once been the gate to the cemetery.

However, we now faced a new problem. Our tour guide, Reb Shlomo Fried, a”h, although a seasoned Breslover who had visited these holy sites several times before, couldn't remember where Reb Noson's kever was. In the past he had entered from a different direction, on the other side of the hill; this approach was unfamiliar to him. We wandered around, searching here and there among the overgrown tombstones, as the light began to fade.

I was standing under Rabbi Noson Maimon's umbrella feeling bereft when suddenly Shira appeared, slightly bedraggled but undaunted. I couldn't believe it!

"What are you doing?" I asked. "I thought you were going to stay in the bus and keep out of the rain!"

"Not me," she retorted, her faced stained with raindrops and flushed from exertion. "I didn't take this trip just to sit in a bus! If you’re going to Reb Noson, so am I!"

This was so moving to me that I was at a loss for words. We both were sharing the chivalrous Rabbi Maimon's umbrella, when another newcomer appeared - someone who had definitely not been on the bus with us. He was a spry old man in his sixties or maybe even his seventies, dressed like a medieval European peasant, with wispy gray hair, clean-shaven, wearing a ragged brown tunic with a thick rope for a belt, a short-brimmed cap that didn’t say “Kangol” on the back, and baggy pants tucked into high boots that almost reached his knees. He leaned on a tall staff and smiled courteously. I gestured questioningly and said "Reb Noson," not knowing one word of Ukrainian to explain further, but no matter - still smiling, the old man nodded in affirmation, pointed down the hill with his cudgel, and quickly ran ahead of us, leeading us straight to our elusive destination.

I tried to pay our deliverer, but he refused any compensation for what he evidently considered simple human decency. However, I pressed a few dollars into his hands, touching my heart to indicate that I understood his feelings but wanted to give him something just to express our gratitude. In the end he nodded his thanks, and hastily disappeared, as we began to recite the psalms of Tikkun ha-Klalli. However, even today I can’t help but wonder: was the old man really the Ukrainian peasant he appeared to be - or was this my second encounter with Eliyahu ha-Novi? If so, I hope he forgave me and my fellow mispallelim for that rude shaloshudes back in Connecticut long ago.

“Make us rejoice, O God, in Eliyahu ha-Novi, Your servant, and in the kingship of the House of Dovid, Your Moshiach, speedily in our days!”

Mipeninei Noam Elimelech

Mipeninei Noam Elimelech