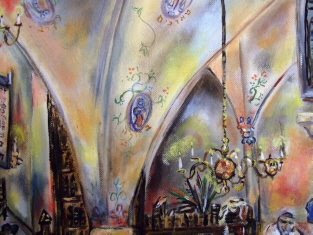

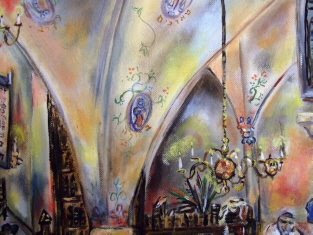

The artist has seen similar decorations, which are frequently old and faded, with moldy stains, and make a slightly primitive impression.

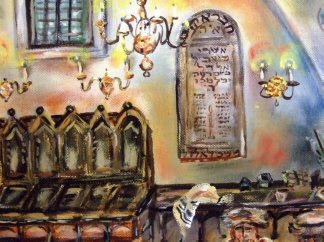

Many shuls in Southern Germany and Middle Europe have light blue, light green, ochre or pinkish walls. If the paint flakes and they are repainted in new colors, and if this process is repeated a few times over several centuries, the walls develop the mixed cloudy pastel patina they have in this painting. In the front of the shul sconces and big brass chandeliers inundate the room in a golden light. All of the candles have been lit in honor of the Yom Tov. A huge brass chandelier with many arms, suspended from the arches and often found in the center of big shuls, has been omitted in this painting, however, since it would block the view of the dancing men.

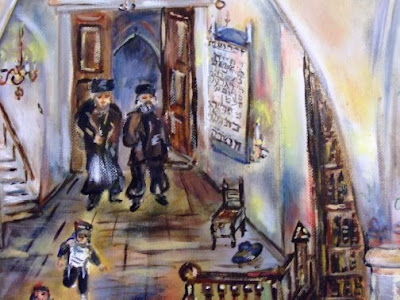

Women’s galleries with carved wooden banisters like those in the painting are often seen in Germany and Holland, the artist’s native country. They are reached by (winding) staircases. A tympanum with grapevines, which the artist included over the side entrance to the sanctuary at the eastern wall of the shul, just to the left of the Aron Kodesh, can be seen in the Alt Neu Shul in Prague. The main entrance to a shul is usually opposite the Aron Kodesh and can’t be seen in this painting, it is hidden out of sight under the women’s balconies. The artist fondly remembered the old patched wooden floors from Holland. At several places, e.g. near the steps leading to the women’s section, clocks and heavy metal tzedakah (charity) boxes have been attached to the wall. As is often the case in such old shuls, not all the clocks work.

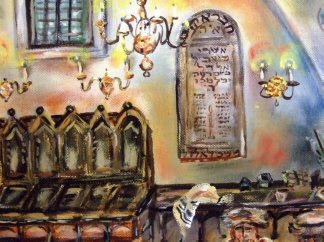

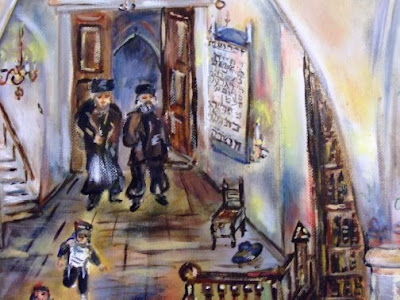

There are several bookcases with prayer books and religious tomes at the eastern wall, the most important wall in the synagogue and usually the spot near the Aron Kodesh, so people can pray facing the direction of Jerusalem. In the right corner are benches and tables, a place to sit and to study. The festival of Sukkos precedes Simchat Torah, and a couple of lulavim and esrogim in little boxes, used during the Chag, have been left by the members of the shul between the books, talesses and bottles of ‘schnapps’ (liquor) which were placed on the table to celebrate Simchat Torah. The furniture of the shul has been pushed to the side to make room for the dancers. The bimah, which in this painting is covered with a red velvet covering, is usually aligned with the Aron, but has apparently been dragged out of the way. The benches are out of sight under the women’s balconies, and a few forgotten rickety chairs with bent backs and an old lectern that is bent out of shape, are left scattered on the floor.

The Names

The Names

Individuals who make important contributions or major donations to a shul, or do something worthwhile for their community, frequently have their own names, and more often, the names of beloved family members who passed away, memorialized on plaques or in other prominent areas (the curtain in front of the Aron Kodesh, the velvet covering of the bimah, Torah mantles or on ceremonial shields). There are three memorial boards in the shul in this painting: a marble one - at the right next to the entrance of the women’s balcony -which is too small for the viewer to read; an old, wooden painted one with slightly faded letters, next to the door in the eastern wall; and a painted wooden one next to the chairs for the rabbi and the important shul members.

In honor of Doctor Goldblum and the zchus (merit) of her family, the memorial next to the door is inscribed with the names of the beloved departed relatives (and one addition of a spouse still alive) of the Goldblum family:

zekher nishmat (in memory of the soul of)

R(eb) Chayyim b’(en) Yisrael (her husband’s father)

M(arat) Rivkah bas Sarah (her husband’s mother, may she live, who is still with us)

R’ Zavell ben Abba Zalman (her father)

T’n’tz’b’h’ (tehee nafsham tzerurim bi-tzror ha-chayyim, may their souls be bundled in the bundle of life, 1 Sam.25:29)

The large board next to the Rabbi’s chair is dedicated to members of the Chevra Maskil el Dal (the aptly named organization: “He who Considers the Poor’). Organizations for the benefit of specific categories of people in need (the poor, orphans, penniless brides etc.) or dedicated to do special good deeds (mitzvoth) such as providing a burial, are ubiquitous in Jewish Communities, and boards to honor their members can be found in many shuls. There is a special reason, however, why the board in the painting is dedicated specifically to an organization with the name Chevra Maskil el Dal. Every Hebrew name of a person is connected with a pasuk, a verse in Tenakh. The name and the verse begin and end with identical letters. The name of Dr.Goldblum's husband is Aryeh, and his verse is: ashray maskil el dal be-yom ra.

The red velvet covering over the bimah is embroidered with the names of the family of Dr.Goldblum:

Aryeh ben Chayyim, (her husband),

Goldah bas Frayda (herself),

Shirah we-Channah (their daughters)

The Aron Kodesh is open and empty, because all the Torah scrolls have been removed to be carried around by the dancers. In the back of the Aron one sees the letters k t, keter torah, the Crown of the Torah. Sometimes the name of an important member of the Community is inscribed in this most honored place, as in this case: Aryeh ben Chayyim, the name of the beloved husband to whom this painting is dedicated.

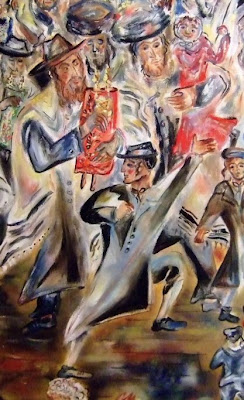

The PeopleThe main theme of this painting is the joyous dancing with the Torah scrolls in honor of the Festival, and the main focus is on the group of dancers in the middle. For artistic reasons, a realistic perspective has been substituted for the medieval concept of representing more important figures (much) larger than the other characters, independent of their position in the composition. This means, that the procession of men in the middle is much bigger than the women on the balcony, which are actually ‘closer’ to the spectator, and the jumping and whirling little groups on the side are smaller then the men in the center, and that the Aron Kodesh is relatively much bigger than the table and the benches at the right side of the painting and the entrances to the women’s balconies.

We see the dancing circle from above, as if one is looking inside the shul from a high window, but the circle seems to jump forward to catch the eye, and realistic perspective proportions of the individuals have been subjugated to aesthetical artistic demands.

The Kehillah (Community) in this painting looks like one of the archetypical small town (shtetl) shuls in Middle Europe at the beginning of the 20th century.

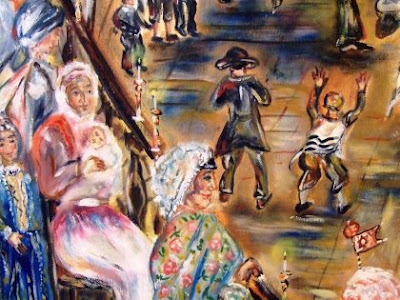

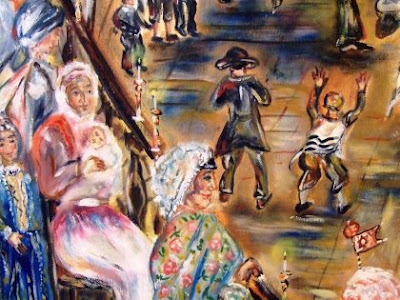

The women wear beautiful silken, embroidered shawls with fringes, flowery dresses, beautiful aprons and white lace bonnets if they are affluent, and simple ‘tichels’ (head kerchiefs) and plain dresses and shawls if they are less affluent. Some look “important”. They are the wives of the wealthy merchants and other prominent members of the community; while others appear rather modest –such as the wives of the talmiday chochomim, the scholars, and the Rebbetzin.

Girls walk around proudly in their new Holiday lace trimmed gowns, or their new caps and ribbons. A little girl stands on a high stool to have a better view. The ladies watch their husbands and sons dance like all women did over the centuries on Simchat Torah. They cuddle their babies and talk with their children and each other, and wave to their little boys who join the dancing, and their little girls who look for tateh (daddy) with their flags and apples. In the front, a bubah (grandmother) ‘shmoozes’ with her ayniklakh (granddaughters).

At the right, a tiny, bent widow, all in black, stands behind two stately matrons with their daughters. Women come and go on the steps to the balconies, children play on the floor. Some crane their necks to see what’s happening downstairs.

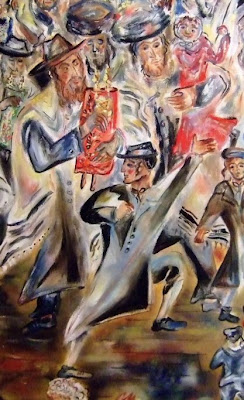

The men are a very mixed group. At this joyous Yom Tov all the Jews of the shtetl gather in the big shul. There are a couple of young and old Chassidim with shtraymels (fur hats), portly and important ‘baleboses’ (house fathers) with hats, married men with a tallis (prayer shawl), young men, lean bokhurs (students), ‘nebachs’ (pitiful souls), wild young boys and serious kids, a boy with a limp and a bad leg next to the yeshiva bokhur (student) in the blue kapota (coat) at the right, proud fathers and grandfathers with their (grand-)children on their shoulders. They carry their two assets which are most dear to them: their Torah and their offspring. There are even some ‘modern’ people who might not be very religious, but enjoy being with the community on such a holy day.

In most shuls some of the young men leave the circle to do some wild dancing, and perform stunts such as somersaults at the side. A nice, simple, poor man sits on a chair and watches, and of course such groups have the full attention of the little boys.

There are usually also some octogenarians present, who enjoy to sit and look, (like the one in the front next to the Aron), and ‘shlufers’ (sleepers), like the man who dozed off at the table in the back, who presumably drank or studied too much the previous evening?

Next to the Aron we see the important son of a Rebbe, with a white shtraymel and a long coat and a smile on his face. The Torah Scrolls all have beautiful velvet mantles, rimmonim (silver ‘turrets’ on top of the holding sticks), crowns and shields, and are embroidered with trees and leaves (the Etz Chayyim, the Tree of Life).

How was the painting made? A few words from the artist.

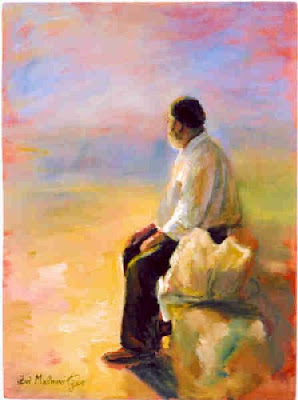

It all started with emails and a visit from Dr.Goldblum, resulting in a commission for a Simchat Torah painting for her husband, in honor of his birthday. Soon afterwards I went to a symposium. One of the lectures was slow and boring, and my thoughts wandered to that large empty canvas that was looming in my studio. I had been thinking about it a lot the last few days. I set up a quick composition sketch in pencil on the back of the program for the lectures: the proportions, the balcony, the Aron Kodesh in the middle and the tentative position of the dancing group. Most of that work had already been done in my head. Usually one small element of a painting starts the whole composition it evolves around. That element in my head is often the reason I actually make the painting. That one line or dab of color, or face or just one hand comes in a flash, and is the beginning of the whole composition. In this case it started with the boy in the front with a raised arm and knee, looking backwards, and the two men behind him, one with a child on his arm, one with a Sefer Torah. Their expression is the same on the canvas as it was in my head. The rest, the shul and all the people, came later. I knew immediately how their face and pose should be, and that they should carry a child that looks straight at the spectator. The boy was inspired vaguely by the pose of a statue which I have seen on the Arc de Triomph in Paris, admittedly an unlikely connection with Simchat Torah, but that is how the human mind works.

I brought the big canvas for this work to my studio in Brooklyn with the help of my husband, by subway, from an art store in Manhattan, in the rain. Putting the big white surface on my easel is a very festive moment for an artist! The actual painting can begin!

The palette is prepared with the right hues and shades, like sienna brown and a bit of cobalt blue, a lot of ochre, cadmium red and zinc white. I use mostly basic colors, which I mix very carefully; that is much more interesting than using all the colors in your artist case, and it promotes unity in all the tones. I had my favorite classical music ready in the studio, tapes with Vivaldi, Mendelssohn, the cello sonatas of Bach, Breslover Niggunim, and a classical radio station.

The composition is set up in basic lines and colors, and a few colors are filled in to get an idea:

In the meantime I was thinking day and night about this work, and started filling in some details in the group of dancers while working on the general composition. Every time you work at a surface it has to dry before you can add other colors or shades, and continue working. Some details, however, are painted ‘wet in wet’, like the faces. This must be done quickly, in one day, to get the original expressions. Darker lines, shades and details are added later, but if the expression is not correct right away it won’t look good later, no matter how many layers you add. All the faces are different, and it was a pleasure to remember all those characters I met over the years and observed in shuls, which I could unceremoniously put into my work. Being an artist gives a lot of freedom! In an early stage the work became very alive!

The Aron gets more detailed

The Aron gets more detailedAlthough I have a general idea, of course, about which people are going to be where (the running boys in the front were in my head from the beginning!), there is always room for improvisation: you look at the floor of the shul in the painting, and you get a strong feeling that in a certain spot you just have to put that toddler on the floor with a flag and an apple next to her:

Memories of your own children and the many Simchat Torah celebrations you have attended in New York and in Europe come up. The people who provided me with my studio have three boys and an extremely cute little girl, watching them is inspiring for this kind of painting. Then the artist has to make choices, like an architect: will the pillars be made out of stone, like those in German Romanesque buildings, or out of wood which is painted in a faux marble, like in many Dutch shuls? Arches or a flat ceiling? A square building or interesting angles? Banisters of wood, many decorations, or an austere sanctuary? Will the floor be wooden, or stone flags? Floors are often a problem. Someone who visited my studio when I had just added the brown ground tones found the floor ‘dull’. Of course it was dull, then; it took more than 20 layers and whiffs and little brush strokes before it even started looking passable. I do not like to show a half finished painting to many people, unless they have a vision of how it will look when it is finished.

I like windows with shimmering greenish glass, which I saw a lot in Leyden (Holland), where I lived for more than 10 years. So the shul got a few classicist windows with round tops. While you are painting them you realize you have to make consoles, and hang up pictures next to them, like the 'shiviti', which does not hang straight. The painting ‘grows’ every day with every brush stroke, and the artist is as curious as anybody else how this will end, although she has more insight and ideas about that. More details are filled in. When you lock your studio in the evening you think already about what must be done the next morning. Sometimes there is an emergency you have to take care of (e.g., we live in an old, badly worn out house where things break all the time), and you cannot paint that day, that really bothered me. I knew from the beginning there would be a door in the east wall, but the idea for the Prague style tympanum I got later, while at work. I have moved a lot in my life, so the question where to put bookcases etc. is not new for me, not in real life and not on canvas. For artistic reasons you have to decide whether the parokhet (the curtain in front of the Aron Kodesh) will be white, like many shuls prefer during the High Holydays, or red, like in many old shuls with an antique interior. Red enhances the composition! Most shuls I visited have some old, rickety chairs standing around, so they were added during a cold afternoon. An artist uses her imagination, to strew around tallesim (prayer shawls) left on a bench, and gets flashes of characters she met in various shuls, like the bent old man resting near the Aron Kodesh (his real life counterparts are from the Lower East Side in New York and from The Hague, Holland) and the boy with the white shtraymel: such a boy lives on our block, we have a shtibel (small Chassidic shul) a few houses down, in an early stage:

And in a later stage:

The boy with a limp is based on somebody we know, too. We often see him hobble by with a book under his arm, on his way to shul.

The perspective choices which have been explained above came naturally; it belongs to my personal style. I prefer this way over a photographic image with a ‘correct’ perspective!

Painting the women’s balconies was a joy, I imagined all types of women I had met or observed at similar balconies in Holland, in Venice, in Berlin and in Williamsburg, New York, and in other places, and I added them and arranged them. It was a lot of patient work. You have to wait between every layer of paint on an embroidered shawl, come back, put in a few lines for a shade or a floral motive, wait again, do the little flowers, highlight the fringes, then the hearts of the flowers etc. It grows under your hands like real embroidery. I thought of my mother, who loves to embroider and is fond of flowery dresses and silken shawls.

There were also set backs during the work. My studio is not heated. I have a little room heater, but certain days it was so cold that this and my fur boots weren’t nearly enough, and the paint became hard and unmanageable on my palette. I had to wait. Then Pesach arrived, with all the cleaning and preparing and some other issues going on which absorbed much more time and energy then I had anticipated, and a nasty flu epidemic hit New York. Then, after the Yom Tov of Shavuos in June, it became hot and humid, and that is also not a pleasant condition to work in. In the summer months I travel, so the work was regularly interrupted. It is a pleasure when you can add the finishing touches. It is like a real house: first you finish the walls, and then the lamps and little details can be added. The chandeliers were added last, the candle flames and the halos. Shadows and extra transparent layers of shadows were led over the walls and the furniture. A last stroke was added to a bench; a red dot on the cheek of a child, and finally the painting was signed. After that it has to dry, the canvas will be taken down from the wooden frame, rolled up, and shipped to Dr. Goldblum, who will hang it in her house and I hope ‘shep nachas’ (get pleasure) of this work which was such a joy to create. During the process I corresponded regularly with Dr.Goldblum, to let her know how it was going, to show photos of progress, and to talk. She provided me the names of her relatives, I started thinking about a good spot to put them in the painting, and one late night got the idea of the Chevra Maskil el Dal. She sent me an email once, asking if it would be a good idea to put in a ‘shlufer’, a man who had fallen asleep, and I just happened to have added such a detail. It was a real pleasure to correspond with her!

The painting is finished, and I have another shul in my memory for Simchat Torah.

Nonstop Joy (Video)

Nonstop Joy (Video)

A teaching from Degel Machaneh Ephraim

A teaching from Degel Machaneh Ephraim