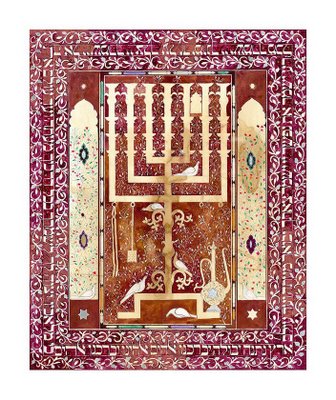

(Picture by M. Rowinski)

Ever since I escaped the hometown of my youth -- overcrowded cockroach-infested cement and steel garbage-strewn car honking sock-in-the-nose New York City -- and retired to the majestic beauty of the Catskills, I have felt that Hashem is somehow nearer to us, or at least is easier to reach, in the untrammeled, or at least not so badly trammeled countryside. Not for nothing did the holy Baal Shem Tov spend his days as a young nistar wandering in the Carpathian mountains in hisbodedus; not for nothing was the Chassidic movement he founded basically a rural phenomenon. One writer from the 1950s described New York City as “six million people hustling for a buck” (fifty years later, make that nine million). Away from the frenzy and artifice of city life, one can get in touch with deeper parts of the soul that lie closer to the core of being than the constantly buzzing conscious mind, conditioned by all the fly-by-day-or-night comings and goings of the forever vanishing world.

As I sat on the porch learning Torah in the summertime, in the shade of a leafy maple tree, I would sometimes pause to gaze upon the nifla’os haBorei surrounding me – and immediately I felt guilty. What does the Mishnah say?

Hamehalekh baderekh v’shoneh u’mafsik mimishnaso v’omer: mah na’eh ilan zeh, u’mah na’eh nir zeh, ma’aleh ‘alav hakasuv k’ilu mischayev b’nafsho (Avos 3:7). [“One who walks along the way, and interrupts his review of his Torah studies and exclaims, ‘How beautiful is this tree! How beautiful is this freshly plowed field!’ Scripture accounts it to him as if he had forfeited his life.”]

I often wondered: is it sinful to contemplate the beauty of nature, which is Hashem’s handiwork? Is reviewing by rote the Torah one has memorized inherently superior to relating in a heartfelt way to the esthetic qualities of the world around us, which is animated by the Creator, as it is written

“Kulam b’chokhmah ‘asisah” (Tehillim 104:24) [“You have made them all with wisdom”]?

One recent Shabbos afternoon I came across an answer to this troubling question.

The late Rav Zvi Yehuda Kook, zal, seems to have been bothered by this Mishnah, too. He shows the error of the commonsense reading of the Mishnah by taking a careful look at the phraseology of the text.

First of all, the Mishnah is discussing a person who is walking and reviewing his Torah studies, and who

then interrupts his learning – not one who is simply strolling through the woods or orchards, etc. The main thing Chazal zero in on is the act of distracting oneself in the midst of Torah study. However, there is a deeper meaning here, as well.

The text states that this person

interrupts his Torah study to extol the beauty of nature. That is to say, he creates a false division between creation and G-d’s Torah. It is for this reason that he “forfeits his life.” The beauty of trees, for which we recite a brokhah every spring, is a Divine gift to humankind. Through contemplating this beauty one comes to love Hashem, as the Rambam states. However, the problem is that this person praises the beauty of nature in context of a hefsek, a “split” or break from the Torah, and not in a state of spiritual connection to the Torah. The intent of Chazal is not to reject this world; rather their intent is to reveal the eternity of the World to Come right here, in the colorful tapestry of the temporal world that we experience.

Rav Zvi Yehudah also proposes a correction of the more common text of the Mishnah, which attributes this saying to Rabbi Shimon. Another girsa attributes it to Rabbi Yaakov (see, for example, the Kehati edition, ad loc.). The younger Rav Kook prefers this version because it is the same Rabbi Yaakov who taught in Avos 4:16: “This world is like a vestibule before the World to Come. Prepare yourself in the vestibule so that you may enter the banquet hall!” And in the following Mishnah (4:17), Rabbi Yaakov taught: “One hour of teshuvah and good deeds in this world is better than the entire life of the World to Come; and one hour of spiritual bliss in the World to Come is better than the entire life of this world!” In all three teachings (including the Mishnah we began with, about one who interrupts his studies to praise the beauty of the tree, etc.), Rabbi Yaakov is consistent with his viewpoint: one must be careful not to lose sight of the goal and essence of things, which is called the “life of the World to Come,” and resist being distracted by the appearance of nature as an end in itself. Then one can successfully relate to this world in keeping with its underlying purpose: as a means of coming to know Hashem.

------------

Based on Sichas Avos ‘al Masechtas Avos (Jerusalem)

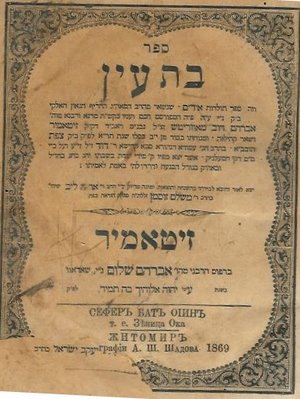

(Picture by

(Picture by