Continued from Part II:Basing his ideas on a Mishnah, Rabbi Nachman’s Likkutei Moharan I, 52 (“Awakening in the Night”), presents an overview of the main practice he taught his followers: hisbodedus -- literally, “seclusion,” but in this context a kind of improvisational prayer and self-examination, ideally conducted in the forests and fields or another natural setting at night.

First, the Mishnah:

“Rabbi Chanina ben Chakhinai used to say: One who awakens in the night, and walks on an isolated path, and turns his heart to empty matters – behold, such a person forfeits his life” (Avos 3:4). The simple meaning is that if a person squanders his time and energy on vain pursuits instead of contributing to civilization, he loses his reason for existence.

While not disagreeing with this, Rabbi Nachman peremptorily turns Rabbi Chanina’s words inside-out and upside-down in order to teach us about the mystic’s quest.

“One who awakens at night” is the intrepid Breslover Chassid who wants to practice hisbodedus / secluded meditation;

“and walks on an isolated path” means that he heads for the countryside, away from human habitation, so that he won’t be affected by any of the thoughts and desires that still linger in the air;

“and turns his heart to empty matters” means that he empties his heart of all negative traits;

“such a person forfeits his life” means (by resorting to an elaborate word-play) that he becomes transformed from the state of a “Contingent Existent” to that of the “Necessary Existent” or “Essential Reality” -- which is Divinity.

Rabbi Nachman builds up to this point by asking how the materialist philosophers could come up with the idea of the eternity of matter – i.e., the mistaken assumption that the universe is a “Necessary Existent” – since even a false idea must begin with a grain of truth. In the course of explaining this mystery, he introduces the concept that by performing God’s will, the Jewish people become reabsorbed in the true “Necessary Existent,” which is God; and in so doing, restore all of the worlds and all elements of creation to the Divine Oneness, along with them. Thus far, the first half of the lesson.

“However,” Rabbi Nachman continues, “to attain this, to become reabsorbed in your Source – that is, to go back and become reintegrated within the Divine Oneness, which is the Necessary Existent – this can only be accomplished through bittul (nullification of ego). You must nullify the ego completely, until you become restored to the Divine Oneness. And it is impossible to come to a state of bittul except through hisbodedus…” Then he goes on to explain what hisbodedus is all about; how the spiritual seeker must get away from the world in order to commune with God, and in the course of hisbodedus work on each negative trait, one after the next, until he reaches the subtlest root of ego – and this, too, can be removed through hisbodedus. Upon achieving bittul, one immediately experiences the Essence of Reality, which is the Divine Unity.

Although their methods are different, Rabbi Nachman’s hisbodedus and Buddhist meditation share similar goals. Both intend to deconstruct illusory mental structures in order to reveal a transpersonal reality of an incomparably higher order of truth.

However, we must remember at which point in his lesson Rabbi Nachman turned off the “main road” to discuss the practice of hisbodedus: right after declaring the necessity of our performing God’s will. This remains our primary responsibility in this world. The attainment of self-nullification in the stillness of the fields through hisbodedus must be combined with performing the mitzvos – with bittul.

I once read that a contemporary Zen Roshi met a prominent figure in the Jewish Renewal movement, and asked what he should teach his Jewish students. The Jewish teacher replied, “Show them how to put on Tefillin in a Zen way.” This actually accords with Rabbi Nachman’s lesson -- if the “Zen way” corresponds to the bittul ha-yesh that is the goal of hisbodedus.

When it comes to self-nullification, there seems to be an overlap between the two paths. However, upon examining Rabbi Nachman’s lesson carefully, we also find two key differences:

1. The Mechuyav HaMetziyus / “Imperative Existent” of Judaism is not only the Buddhist “Ground of Being,” but the God of revelation Who, through the mystery of prophecy, gave Israel the Torah. God not only exists and creates, but commands and claims. Thus, much of Judaism is about service, instead of meditative absorption.

2. The primary task of Israel is to perform the commandments, which are God-given, and which in both a practical and mystical sense refine and transform creation.

It is true that Mahayana Buddhism in particular has a “this-worldly” side in its ethic of seeking the benefit of all beings (i.e., the Bodhisattva Vow). But this is not the same thing as the Jewish people’s performance of mitzvos, which are specific divine mandates, and not just “good deeds.” Some mitzvos called chukkim (“decrees”), like the ritual of the Red Heifer, completely surpass human understanding. The complex Jewish dietary laws also fall into this category, although the kabbalists reveal some of the reasons behind them. The task of studying the Torah and performing the 613 mitzvos uniquely rests on the Jew. On some level, as Jews, we all know this, and feel unfulfilled if we fail to accomplish our mission.

This is not meant to be a weighty burden. The holy ARI (Rabbi Yitzchak Luria, sixteenth century) attributed the high spiritual levels he reached to “simchah shel mitzvah,” rejoicing in the performance of the commandments (see Mishnah Berurah 669:11; cf. Likkutei Moharan I, 24:2). Why did he feel this way? And why should we feel this way? For the simple reason that to a Jew who believes in God, the mitzvos connect the one who performs them with the One Who gave them.

The kabbalists describe the 620 mitzvos (613 Torah mitzvos plus seven rabbinic mitzvos) as “620 columns of light” (Rabbi Moshe Cordovero, Pardes Rimonim 8:3). (620 is the numerical value of Keser / Crown, the highest of the ten sefiros and locus of the Divine Will.) Chassidic master Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi explains this to mean that the mitzvos are actually spiritual channels by which we connect to the Divine Will at their root (Tanya, Iggeres HaKodesh, Letter 29). That is, we become instruments of the Divine Will and therefore bound to God in a manner that transcends the limitations of intellect. For one who takes this to heart, performing a mitzvah is a source of boundless joy.

Breslover Chassidism would say that we need both factors: bittul, which comes through hisbodedus, and the mitzvos, which connect us to the divine purpose in creation in the here and now – and which enable us to fulfill our unique mission as Jews. “Know Him in all your ways,” the Psalmist declares. This is the source of Chassidic joy.

The Mixed Blessing of Dualism: The metaphysical villain is dualism – estrangement from the Primordial Unity; yet dualism makes it possible for us to have a relationship with G-d and with each other. One of the meanings of the Torah’s story of how Eve was separated from Adam is that this alludes to how creation was “separated” from the Creator, all so that we might have a relationship. This is the positive meaning of creation. Dualism is not just an illusion or spiritual obstacle to overcome, but the necessary precondition for having a relationship. This, too, is the meaning of the Song of Songs, which is an allegory of the love between God and the Jewish people, who serve Him through the Torah and mitzvos.

Yet at the same time, dualism goes hand in hand with the ego, which blocks the road back to God and distorts our spiritual vision. How can we get out of this conundrum? Rabbi Nachman alludes to this problem and its solution in one of his thirteen mystical stories, “The Tale of the Seven Beggars.”

The Heart and the Spring: In this sub-plot of the tale, the third holy beggar materializes out of thin air at the wedding feast of two orphans, who are the story’s protagonists. He is the Beggar with the Speech Defect – whose apparent deficiency masks his greatest spiritual power. He claims that his parables and lyrics contain all wisdom – and the “proof” he offers is the testimony of the True Man of Kindness.

The Beggar with the Speech Defect goes around and gathers up all true kindness in the world and brings it to the True Man of Kindness, who presides over time. In the merit of the human acts of kindness he receives, the True Man of Kindness gives a new day to the Heart of the World, who gives it to the Spring, thereby sustaining the universe.

How so? On the top of a certain mountain, there is a stone, out of which flows a wondrous Spring. At the other end of the world, stands the Heart of the World, which longs and yearns and cries to go to the Spring. The Spring also yearns for the Heart. However, the Heart cannot go to the Spring – for if it came too close, it would no longer be able to see the peak from which it flows. And if it stopped looking at the Spring for even an instant, the Heart would perish; and with it, the entire world, which receives its life-force from the Heart. Therefore, the Heart stands facing the Spring, yearning and crying out.

The Spring transcends time. Therefore it only possesses the time that it receives from the Heart as a gift for one day.

When the end of the day draws near, they begin to part from one another with great love and wonderful poetry. Watching over all this, the True Man of Kindness waits until the last minute and then gives the Heart a gift of one more day. The Heart immediately gives the day to the Spring, and thus the world endures. Yet everything depends upon the Beggar with the Speech Defect, who collects all of the true kindness, in the merit of which time comes into existence. Therefore, all of the wondrous parables and lyrics are his, too.

This story, like all of Rabbi Nachman’s tales, has multiple levels of meaning, rooted in the mysteries of the kabbalah. On one level, the Heart and the Spring is an allegory about the primacy of our relationship with God, which is like a marriage. (This, too, is why Judaism is not a monastic tradition, but places so much emphasis on marriage. Indeed, the marriage relationship is called “kiddushin” or “sanctification” for two reasons: because each partner becomes “kadosh” or designated to the other; and because marriage is intrinsically holy. It is a spiritual relationship, which challenges us to get past our innate selfishness, to cease to be mere “takers” and become “givers.” The tale of the Heart and the Spring also indicates why the sculpted forms of the K’ruvim, male and female winged angels, hovered over the Ark of the Covenant in the inner sanctum of Holy Temple. Their embrace represents “unity in dualism.”)

We relate to God with the longing of the Heart for the Spring atop the faraway mountain. The “catch” is to realize that God is present on both sides of the relationship.

The vehicle for attaining this perception is hisbodedus. As third-generation Breslov scholar Rabbi Nachman Goldstein, the Rav of Tcherin, wrote:

“The perfection of hisbodedus is to attain deveykus – to cleave to God until you become utterly subsumed within the Divine Oneness. The word hisbodedus is a construct of badad, meaning either ‘seclusion’ or ‘oneness,’ as in the phrase ‘they shall be one with one [i.e., of equal weight]’ (Rashi on Exodus 30:34). That is, you must become ‘one with God’ to the extent that all sensory awareness ceases, and the only reality you perceive is Godliness. This is the mystical meaning of the verse, ‘Ein ode milvado . . . There is nothing but God alone’ (Deuteronomy 4:35). This, too, is why the Torah calls Israel ‘a people that dwells alone [badad]’ (Numbers 23:9). The destiny of each Jew is to attain complete unification with God, without any intermediary” (Zimras Ha’aretz, I, 52; translated in “The Tree That Stands Beyond Space,” p. 83).

In hisbodedus – if one succeeds in “breaking through” – one discovers that God stands on both sides of the relationship. In a sense, God davens (prays) to Himself.

If Zen master Hakuin, famous for his consciousness-altering koans (conundrums), were a Breslover Chassid, he might say that this is the “sound of one hand clapping.”

--

There will be a follow-up to this series about Rabbi Nachman’s teachings concerning silent meditation.

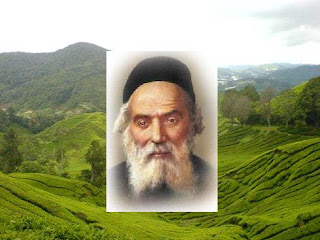

(Picture courtesy of timyoung.net)

(Picture courtesy of timyoung.net)