A Simple Jew

אַשְׂכִּילָה בְּדֶרֶךְ תָּמִים

Sunday, December 14, 2008

Friday, December 12, 2008

Crossing The Dniester

כִּי בְמַקְלִי, עָבַרְתִּי אֶת-הַיַּרְדֵּן הַזֶּה

With my staff I crossed this Jordan. (Bereishis 32:11)

Degel Machaneh Ephraim, Parshas Vayishlach:

One can further explain this along the lines of that which my master, my grandfather [the Baal Shem Tov] related: Once he crossed the Dniester River without using any name; instead, he laid down his gartel, and crossed upon it. He said that it was with great emuna that he crossed.

The Outer Trappings Of Piety

הַצִּילֵנִי נָא מִיַּד אָחִי, מִיַּד עֵשָׂו

Deliver me, from the hand of my brother, from the hand of Esav. (Bereishis 32:12)

Degel Machaneh Ephraim, Parshas Vayishlach:

This should be interpreted in accord with that stated in the Midrash: In the future, Esav will wrap himself in tzitzis and sit among the tzaddikim, and Hashem will pull him down from them.

It is important to say that this is also common in this world because of our many sins; for falsehood has increased in the world, and everyone wants to ascend to the level of the completely faithful in Israel. He sees that they are dressed in white clothing on Shabbos and wear a tallis on Erev Shabbos during Mincha and says, "I can surely be like them."

It is this which is more difficult than all else, for this causes the golus to be lengthened: they are called the Erev Rav, for this are mixed in among the Jewish people and it is difficult to separate them. Like wheat: the chaff and straw which is not all that stuck to the wheat is dispersed easily; but the refuse that is in the wheat is attached and it is hard to remove.

On A Winter Friday Night

On a winter Friday night, one can attain levels that can be reached on Kol Nidrei night. In the winter, the nights are long and one can serve Hashem the whole night long.

(Reb Nosson of Breslov)

Thursday, December 11, 2008

Question & Answer With Rabbi Betsalel Edwards - Committing Aveiros In Our Dreams

A Simple Jew asks:

To what degree should we be concerned about the aveiros that we commit in our dreams?

Rabbi Betsalel Edwards answers:

To what degree should we be concerned about the aveiros that we commit in our dreams?

Rabbi Betsalel Edwards answers:

We may be concerned, because often one dreams about the thoughts he entertains during the day. Be honest with yourself to ascertain if this is indeed the case. But remember that it is not at all so simple, and often we find that dreams and reality do not always see eye to eye. In other words, our tradition teaches us that something appalling in waking reality could be an omen of something quite good if found in a dream. By way of example, we find in the Gemara (Berachot, 57a):

If one dreams that he has intercourse with his mother, he may expect to obtain understanding, since it says, 'You will call understanding 'mother'.' If one dreams he has intercourse with a betrothed maiden, he may expect to obtain knowledge of Torah, since it says, 'Moses commanded us a law (the Torah), an inheritance of the congregation of Jacob.' Read not morashah [inheritance], but me'orasah [betrothed]. If one dreams he has had intercourse with his sister, he may expect to obtain wisdom, since it says, 'Say to wisdom, you are my sister.' If one dreams he has intercourse with a married woman, he can be confident that he is destined for the future world, provided he does not know her and did not think of her in the evening.

So we see that when found in dreams, our sages saw deplorable sins such as incest or adultery as metaphors for noble pursuits such as Torah knowledge.

Always seek to derive a good interpretation even for a bad dream, for the fulfillment of dreams follows the interpretation. Also in the Gemara (Berachot, 55b):

Rav Bana'ah told that there were twenty-four interpreters of dreams in Jerusalem. Once I dreamt a dream and I went round to all of them and they all gave different interpretations, and all were fulfilled, thus confirming that which is said: All dreams follow (interpretation of) the mouth.

Still, many dreams can be disturbing, and Chazal gave us advice as to how to deal with and even neutralize the negative aspects of a dream. Sometimes a fast may be warranted. The Shulchan Aruch (Orach Haim, 220:1) teaches, "If one has a dream that disturbs him, he may ameliorate it by gathering together three friends, and let them together say before him, "you saw a good dream." Then you should answer, "it was good, and it shall be good."

The Rushing Current

Let neither the current of water sweep me away, nor the deep swallow me, and let a well not close its mouth over me. Answer me, Hashem, for Your kindness is good; according to Your abundant mercies, turn to me.

(Tehillim 69:16-17)

Wednesday, December 10, 2008

Question & Answer With Neil Harris - A Black Knitted Yarmulke

A Simple Jew asks:

What prompted you to recently switch from wearing a black velvet yarmulke to a black knitted yarmulke?

Neil Harris answers:

What prompted you to recently switch from wearing a black velvet yarmulke to a black knitted yarmulke?

Neil Harris answers:

I have, until two weeks ago, worn a black velvet for the past seven years. Before that I had worn a black knitted for ten years.

Since Rosh Hashana I had been debating about making the switch back. Initially I had switched to velvet when I was living in community of about thirty shomer Shabbos families. I had thought then that based on my current outlook on things and that I was one of a handful with any formalized yeshiva background (after finishing public high school) that wearing a velvet yarmulke would somehow strengthen my own yiddishkeit within a community in which my Torah observance placed me in the minority. It was, at the time, the right move, I think.

Over the past two years, though I felt that part of my personality had sort of been confined by my own doing. I had found myself restricted by the, for lack of a better phrase, image of "right-of-center-yeshivish" connotation of a black velvet. I hadn't given up part of who I was, but I could tell that I was downplaying parts of my personality. I saw myself slowly falling prey to small signs of frumkeit (emphasis on the external trapping of being frum resulting in false-piety). While this wasn't due totally to wearing a velvet yarmulke, I became aware that somewhere down the line I had begun to change. This troubled me, because that not what I'm really all about. I try to stay clear of things relating to frumkeit.

During the days between Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur I realized that I really needed to get "back to basics" in terms of my Avodas Hashem and the things that I initially loved about Yiddishkeit when I became observant. Since then I have gone back once again read, with a new perspective, many seforim that have sat on my bookshelves, seforim that I felt I had "out grown". As I attempted to refresh my Yiddishkeit I decided that sporting a velvet yarmulke wasn't something that reflected me and I returned back to a black knitted yarmulke.

When it comes to issues of chizonius (external) and penimius (internal) expressions of our Yiddishkeit there's a time and a place for each. Each of us has to know when to make the call.

Gid Hanasheh

At the root of this mitzva lies the purpose that the Jewish people should have a hint that even though they will endure great tribulations in their exiles at the hands of the nations and the descendants of Esav, they should remain assured that they will not perish, but their offspring and name will endure forever, and a redeemer will come and deliver them from the oppressor's hand. Remembering this matter always through this mitzvah, which will serve as a reminder, they will stand firm in their emuna and righteousness forever.

(Sefer HaChinuch)

Tuesday, December 09, 2008

The Dividends Of Enduring Stress

Work has been incredibly stressful since Rosh Hashana. At times, it seems as if it was decreed that I would not enjoy tranquility this year. There have been days within the past few weeks that have been so difficult to deal with that I have woken up dreading to go into the office and felt a pit in my stomach and a tightness in my chest for the entire work day.

Despite enduring day after horrible day at the office, I made sure to leave the office at the office. I repeatedly fought off any thoughts of work as soon as I left for the day and made sure not to take out any of my frustrations on my family when I returned home.

After one particularly stressful week, my wife remarked to me that she noticed that I was dealing with our four year-old son with much more tolerance and patience than I normally did, and as a result his behavior at home had favorably improved. She also told me that his nursery school teacher had mentioned that he seemed happier and more well behaved during the course of the day.

Hearing these words from my wife helped me put what I was going through in a greater perspective; accepting the stress as a necessary means to help me improve my relationship with my son.

12 Cheshvan Links - יב כסלו

A Fire Burns in Breslov: It all depends on your thoughts and attitude

Dixie Yid: Israel vs. The Five Towns

Heichal HaNegina: The HOMELESS Mizmor L'David

Life in Israel: Rabbi Grossman sings (video)

Without A Sound

When words and cries don't help, cry deep in your heart without letting out a sound.

(Rebbe Nachman of Breslov)

Monday, December 08, 2008

Question & Answer With Dixie Yid - Forcing Happiness

A Simple Jew asks:

The Degel Machaneh Ephraim stressed the importance of constantly thinking happy thoughts by noting that the letters of the word מחשבה (thought) are identical to the phrase בשמחה (in joy). Rebbe Nachman of Breslov taught that being b'simcha is one of the most difficult things, and said, "It is harder than all spiritual tasks."

Have you found that there are times that you must literally force yourself to be happy? To what degree have you focused on this issue of being b'simcha in your avodas Hashem?

Dixie Yid answers:

The Degel Machaneh Ephraim stressed the importance of constantly thinking happy thoughts by noting that the letters of the word מחשבה (thought) are identical to the phrase בשמחה (in joy). Rebbe Nachman of Breslov taught that being b'simcha is one of the most difficult things, and said, "It is harder than all spiritual tasks."

Have you found that there are times that you must literally force yourself to be happy? To what degree have you focused on this issue of being b'simcha in your avodas Hashem?

Dixie Yid answers:

For me, the way that I generally keep my happy equilibrium is by having trained myself to be indifferent to most things. Perhaps you could share with me whether you think this approach is good or bad, though I'm not sure to what extent I could change it at this point.

It all started way back in ancient times when I was in 9th grade. I had some good friends who shared their problems with me. For a while, my daily mood was dependent on how my friends were doing. When they shared difficulties with me, I would be depressed. When they were happy, I was happy. Eventually, I developed an emotional distance so that even when I was able to be a friend who was there for his friends and who was able to listen, I was not personally affected by the troubles that my friends were going through. I think this attitude has spread through my life in general.

Although when there are extraordinarily bad or good things are going on in my or my family's life, I am affected emotionally, I am generally calm, happy, and steady through the vast majority of life's days.

I am not entirely sure that this is due to a high level of Bitachon, where I have absolute trust in the one Who Spoke and the world came into being. I do not think that I can say that I am fully engaged with my own and others suffering or worries, and yet am still able to maintain my Trust in G-d as the basis for my happy go lucky demeanor.

Rather, I think that it would be closer to the truth to say that I keep myself comfortably distant and unconscious of both other people's worries and my own. On balance, I think this keeps me happier, though it does drive my wife crazy!

Should I just be thankful that I am not phased by most of what is thrown my way in life? Or should I worry that I'm not able to have both happiness and total engagement with my world? What do you and your readers think?

11 Kislev Links - יא כסלו

A Simple Jew: Not Mere History

Chabakuk Elisha: Dina

Dixie Yid: How To Give Over Yiddishkeit (Audio Shiur)

Chabakuk Elisha: Singing In Defeat

A Professional Soldier

We all want to come to the level where we no longer experience certain thoughts and desires and are free to deal with other challenges. However, it is very possible that we will never reach that point, that we are by nature beinonim who must engage in this struggle our entire lives.

A beinoni is a professional soldier. He was not created to live in a safe, protected haven. Rather, his job is to battle on behalf of

G-d, overcoming the sitra achra within himself.

(Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz)

Friday, December 05, 2008

Question & Answer With Yossi Katz - Sefer HaMiddos

A Simple Jew asks:

Rabbi Avraham Sternhartz once said:

"Each and every aphorism of Sefer HaMiddos (the Aleph-Beis Book) requires study and serious analysis. They are the very basics of the Torah and wondrous morsels of wisdom; insights and revelations filled with intelligence and the knowledge of G-d which the Ancient of Days had concealed."

Compared with Likutey Moharan, Likutey Halachos, Sichos HaRan, Likutey Eitzos, and Sippurei Maasios, to what degree is Sefer HaMiddos routinely learned by Breslover Chassidim today?

Yossi Katz answers:

Out of all the Breslover seforim that were mentioned I would definitely have to say that Sefer HaMiddos is studied the least. I am not aware of any Breslov groups or leaders who specifically recommend studying Sefer HaMiddos in any kind of specific "routine." Although Breslover Chassidim do believe in studying all the seforim on a constant basis and striving to finish them as many times as possible. It is my opinion that the reason for this is not because of any disrespect for Sefer HaMiddos, for as you quoted in the name of Rabbi Avraham Sternhartz, "Each and every aphorism of Sefer HaMiddos (the Aleph-Beis Book) requires study and serious analysis."

I do not believe there is a Breslover that would disagree with that statement. In my opinion the reason for this is because it is often very difficult to apply the statements in the sefer in any kind of practical way, which is something so central to Breslov Teachings. I will give one quick example based on just randomly opening the sefer, "When one is building a wall and his kippah falls off, know that this is a bad sign G-d forbid for his children." (Bayis, Chelek II, VI) In contrast to the other seforim, if one has enough Seyata D'Shmaya, he can live his whole life, or long periods of time based on a sole lesson in Likutey Moharan, or Halacha in Likutey Halachos.

For those interested, about a year ago, Rabbi Vitriol of Williamsburg put out a beautiful version called Tifferes HaMiddos with expanded references based on Midrash, Shas etc... This work as well as other Breslover Seforim can be purchased through Rabbi Gorelick 845-807-2783.

Rabbi Avraham Sternhartz once said:

"Each and every aphorism of Sefer HaMiddos (the Aleph-Beis Book) requires study and serious analysis. They are the very basics of the Torah and wondrous morsels of wisdom; insights and revelations filled with intelligence and the knowledge of G-d which the Ancient of Days had concealed."

Compared with Likutey Moharan, Likutey Halachos, Sichos HaRan, Likutey Eitzos, and Sippurei Maasios, to what degree is Sefer HaMiddos routinely learned by Breslover Chassidim today?

Yossi Katz answers:

Out of all the Breslover seforim that were mentioned I would definitely have to say that Sefer HaMiddos is studied the least. I am not aware of any Breslov groups or leaders who specifically recommend studying Sefer HaMiddos in any kind of specific "routine." Although Breslover Chassidim do believe in studying all the seforim on a constant basis and striving to finish them as many times as possible. It is my opinion that the reason for this is not because of any disrespect for Sefer HaMiddos, for as you quoted in the name of Rabbi Avraham Sternhartz, "Each and every aphorism of Sefer HaMiddos (the Aleph-Beis Book) requires study and serious analysis."

I do not believe there is a Breslover that would disagree with that statement. In my opinion the reason for this is because it is often very difficult to apply the statements in the sefer in any kind of practical way, which is something so central to Breslov Teachings. I will give one quick example based on just randomly opening the sefer, "When one is building a wall and his kippah falls off, know that this is a bad sign G-d forbid for his children." (Bayis, Chelek II, VI) In contrast to the other seforim, if one has enough Seyata D'Shmaya, he can live his whole life, or long periods of time based on a sole lesson in Likutey Moharan, or Halacha in Likutey Halachos.

For those interested, about a year ago, Rabbi Vitriol of Williamsburg put out a beautiful version called Tifferes HaMiddos with expanded references based on Midrash, Shas etc... This work as well as other Breslover Seforim can be purchased through Rabbi Gorelick 845-807-2783.

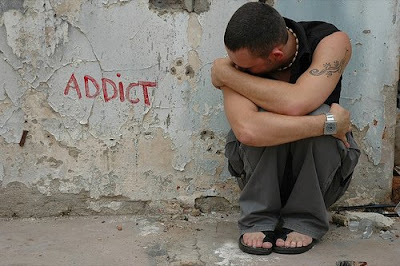

"Understanding" A Person's Essence In 30 Seconds

Long Beach Chasid commenting on Naivete & Tzedaka:

It's really sad that we think we have the ability to understand a whole person's essence by the 30 seconds you scan them up and down with our eyes.

Who are you to decide if someone is an addict or what they are going to do with the money?

It's a dollar. Even if you gave the same guy a dollar every day you are allowed to handle money that still comes out to less than $300 a year.

I know for most people $300 is not even 50% of what you are required to give.

A Rebbe once said that Hashem makes dishonest beggers so we aren't held accountable for rejecting the honest ones.

Even if someone is an addict they have to at some point eat food or drink some water or they will die. Its not hard science.

So what if this addict needs some food this time around?

If you are all on such a high level that you can see the whole picture, that's amazing to have such holy insight into the world.

As for me, ill just risk giving a dollar and performing a mitzvah with Joy.

The Baal Shem Tov says that when you give tzeddakah you create the holy name of Hashem.

The Yud is the money The Hey is your hand the Vav is his arm extending and the Hay is his hand receiving.

If you see a homeless many run with joy to perform the mitzvah before he has to degrade his dignity in asking.

Who knows, that "crack addict" could be Elijah HaNavi.

It's really sad that we think we have the ability to understand a whole person's essence by the 30 seconds you scan them up and down with our eyes.

Who are you to decide if someone is an addict or what they are going to do with the money?

It's a dollar. Even if you gave the same guy a dollar every day you are allowed to handle money that still comes out to less than $300 a year.

I know for most people $300 is not even 50% of what you are required to give.

A Rebbe once said that Hashem makes dishonest beggers so we aren't held accountable for rejecting the honest ones.

Even if someone is an addict they have to at some point eat food or drink some water or they will die. Its not hard science.

So what if this addict needs some food this time around?

If you are all on such a high level that you can see the whole picture, that's amazing to have such holy insight into the world.

As for me, ill just risk giving a dollar and performing a mitzvah with Joy.

The Baal Shem Tov says that when you give tzeddakah you create the holy name of Hashem.

The Yud is the money The Hey is your hand the Vav is his arm extending and the Hay is his hand receiving.

If you see a homeless many run with joy to perform the mitzvah before he has to degrade his dignity in asking.

Who knows, that "crack addict" could be Elijah HaNavi.

Eating & Drinking

A person must sanctify himself in eating and drinking more than in learning and davening.

(Noam Elimelech)

Thursday, December 04, 2008

Compared To A Dream

Golus can be compared to a dream. During sleep one sees in a dream things which are false, for a dream is something imagined and not true. So it is with golus: it is like sleep and a dream in which one does not know the truth nor the true purpose. It consists solely of the things which seem to be true to each individual.

(Degel Machaneh Ephraim)

Wednesday, December 03, 2008

Question & Answer With Rabbi Shais Taub - Approaching Tanya

A Simple Jew asks:

What lessons have you learned about how to best approach learning Tanya over the years you have spent learning it? How do you feel that your understanding has developed since the first time you picked up this sefer?

Rabbi Shais Taub answers:

You knew this question would be too irresistible for me to pass up. As you know, I am pretty fanatic about Tanya. As an aside, I 'd like to mention that I think the reason why I have spent so much time trying to understand this particular book is because of it's structure. The structure of Tanya blows me away. Contrary to what seems to be an unspoken but popular misconception, Tanya is not just a compilation of chasidic ideas. Indeed, Tanya is the Torah she'b'ksav chasidus. But Torah she'b'ksav does not mean cholent. It's not like the Alter Rebbe just went and crammed in as much chasidus as he could fit into one small book. Tanya has a structure. Tanya is an orderly system that takes you step-by-step through the inevitable challenges faced by one seeking to be of better use to his Maker and his fellows. In my opinion, Tanya is not a book. It's a program.

Which leads me to answer your first question...

What lessons have I learned about how best to approach Tanya? Very simple. Never forget the purpose of the book. The Alter Rebbe wrote Tanya because he wanted to provide a substitute for one-on-one meetings with him where you could pour out your heart and then receive guidance tailor-made for your unique situation. How do I know that this is why the Alter Rebbe wrote Tanya? Because that's what he says in his Introduction. Tanya is a face-to-face meeting with a spiritual master who listens and gives guidance to each and every one of his followers. Tanya is not an encyclopedia of Chasidus. It is a transcript of your yechidus with the Alter Rebbe. It follows an orderly and natural progression. The questions you're asking the Alter Rebbe later in the book are on a higher level than the questions you were asking at the beginning. There is a real growth that you can see happening to the one to whom the Alter Rebbe is speaking.

So, whenever I study or teach Tanya, I always keep in mind, "How did we get from there to here? What was I supposed to have done in the last chapter that has made me ready to hear what the Alter Rebbe is now telling me in this chapter?"

I didn't start studying Tanya until I was 22. I learned Perek Aleph with my cousin one Friday night while I was visiting him at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. I couldn't figure out if I was a tzaddik, a rosho or a beinoni. The next day, after shul, we were at Rabbi Yona Matusof's house, so I asked Rabbi Matusof. He didn't give me a straight answer, which annoyed me.

Anyway, when I went to yeshiva, I started learning Tanya on my own and more in-depth. I remember once sitting at a farbrengen at Hadar HaTorah where the mashpia, Rabbi Wircberg, was quizzing the bocherim about the general concepts of each perek. He was saying stuff like, "18 is ahavah mesuteres, 29 is timtum halev, 32 is ahavas yisrael." I couldn't catch all of it. Only some of it sounded familiar. What impressed me was that he was going in order, chapter by chapter. It suddenly dawned on me that this book, although it had no Table of Contents, was highly structured. I was also ABSOLUTELY CERTAIN that (get a load of this) EVERYONE who studied Tanya since they were kids, ALL know what each perek is about and how one perek connects to the next. I felt extremely inadequate.

A few years later, I was married already and I was teaching in mesivta. One Yud Tes Kislev, I was all alone and I made a hachlata. I decided, "Enough already. I want to understand the structure of Tanya! I want to know what each perek DOES and how it brings us to the next perek. What chapters are thematically grouped and why does one group come before the next? I am going to make a MAP of Tanya." So, I sat down and started working feverishly. I read everything I could get my hands on that would explain the flow and structure of Tanya. Of course, there was the Tzemach Tzedek's Kitzur of Tanya but I also read everything else I could find. I would comb through Shiurim B'Sefer HaTanya looking for the little introductions at the beginnings of the chapters that would explain how we got to this chapter from the last chapter. Also, particularly helpful was Nissan Mindel's introduction to the English translation of Tanya. There, he lays it all out as far as the structure of the book.

Anyway, I worked on this "map" of Tanya, which was really just my handwritten notes which I later typed up on the computer. I was finished by Chof-Daled Teves, the Alter Rebbe's yahrzeit which was five weeks from the time that I had started. I didn't sleep much during that time.

Well, eventually the map was published by Kehos. I had to re-edit it a little bit and of course, all of the graphic design elements needed to be constructed, but basically, the whole map was done between Yud-Tes Kislev and Chof-Daled Teives, 5763 (the winter of 2003). I also had to make one major structural change in the map which was based on a comment by R' Yoel Kahan. The way I had the map was that 33 and 34 begin the theme of Moshiach which is continued until 37. R' Yoel said that 33 and 34 are a continuation of the PREVIOUS group of chapters, 26-31, which speak about joy. The fact that chapter 32 interrupts the flow is precisely that, an interruption, added later by the Alter Rebbe, but the theme begun in 26 really continues until 34.

A couple of years ago, the JLI (Jewish Learning Institute) asked me if I could turn the map into the basis for a curriculum on Tanya. Of course, I was very excited to take on the project. The way I devised the course was to really try to bring out that although we cannot possible do justice to Tanya in 6 weeks, we CAN give you a feel for its structure in that amount of time. Each week, the course presents another phase of development. There's a certain closure at the end of each lesson where the person feels, "Now I've got it." Then, they go out and try to live perfectly with that information alone and they hit a wall. The come back next week desperate for another meeting with the Alter Rebbe because they need the next piece of advice to get them through the next phase. It's really neat watching students go through the steps of Tanya like that. And the most important thing is that they achieve this growth by going through the Tanya IN ORDER. I think that sometimes, we do a disservice to our students when we present them with "themes" in Tanya. We try to pick out all the chapters from all over Tanya that mention one concept and then put them all together and teach them. That's like playing a symphony for someone by first playing them all of the F's and then all of the E's and so on.

Just the other day, someone told me that 14,000 students all over the world are currently taking the JLI course on Tanya and that this is the biggest course in Tanya ever. It's really exciting to think of all these thousands of Jews who are going to have tasted what it's like to really live with the Tanya. I'm fully expecting an all out revolution to come from this.

Now, I'll try to answer your second question.

How do you feel that your understanding has developed since the first time you picked up this sefer?

The more I learn Tanya, the more I discover about it that I completely don't understand. The Rebbe Rashab said that our understanding of Tanya is like a goat looking at the moon. All I can say is that, they very little bit of Tanya that I do understand (or that I think I understand) has changed my life and helped me to give other people the tools to change their lives as well.

What lessons have you learned about how to best approach learning Tanya over the years you have spent learning it? How do you feel that your understanding has developed since the first time you picked up this sefer?

Rabbi Shais Taub answers:

You knew this question would be too irresistible for me to pass up. As you know, I am pretty fanatic about Tanya. As an aside, I 'd like to mention that I think the reason why I have spent so much time trying to understand this particular book is because of it's structure. The structure of Tanya blows me away. Contrary to what seems to be an unspoken but popular misconception, Tanya is not just a compilation of chasidic ideas. Indeed, Tanya is the Torah she'b'ksav chasidus. But Torah she'b'ksav does not mean cholent. It's not like the Alter Rebbe just went and crammed in as much chasidus as he could fit into one small book. Tanya has a structure. Tanya is an orderly system that takes you step-by-step through the inevitable challenges faced by one seeking to be of better use to his Maker and his fellows. In my opinion, Tanya is not a book. It's a program.

Which leads me to answer your first question...

What lessons have I learned about how best to approach Tanya? Very simple. Never forget the purpose of the book. The Alter Rebbe wrote Tanya because he wanted to provide a substitute for one-on-one meetings with him where you could pour out your heart and then receive guidance tailor-made for your unique situation. How do I know that this is why the Alter Rebbe wrote Tanya? Because that's what he says in his Introduction. Tanya is a face-to-face meeting with a spiritual master who listens and gives guidance to each and every one of his followers. Tanya is not an encyclopedia of Chasidus. It is a transcript of your yechidus with the Alter Rebbe. It follows an orderly and natural progression. The questions you're asking the Alter Rebbe later in the book are on a higher level than the questions you were asking at the beginning. There is a real growth that you can see happening to the one to whom the Alter Rebbe is speaking.

So, whenever I study or teach Tanya, I always keep in mind, "How did we get from there to here? What was I supposed to have done in the last chapter that has made me ready to hear what the Alter Rebbe is now telling me in this chapter?"

I didn't start studying Tanya until I was 22. I learned Perek Aleph with my cousin one Friday night while I was visiting him at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. I couldn't figure out if I was a tzaddik, a rosho or a beinoni. The next day, after shul, we were at Rabbi Yona Matusof's house, so I asked Rabbi Matusof. He didn't give me a straight answer, which annoyed me.

Anyway, when I went to yeshiva, I started learning Tanya on my own and more in-depth. I remember once sitting at a farbrengen at Hadar HaTorah where the mashpia, Rabbi Wircberg, was quizzing the bocherim about the general concepts of each perek. He was saying stuff like, "18 is ahavah mesuteres, 29 is timtum halev, 32 is ahavas yisrael." I couldn't catch all of it. Only some of it sounded familiar. What impressed me was that he was going in order, chapter by chapter. It suddenly dawned on me that this book, although it had no Table of Contents, was highly structured. I was also ABSOLUTELY CERTAIN that (get a load of this) EVERYONE who studied Tanya since they were kids, ALL know what each perek is about and how one perek connects to the next. I felt extremely inadequate.

A few years later, I was married already and I was teaching in mesivta. One Yud Tes Kislev, I was all alone and I made a hachlata. I decided, "Enough already. I want to understand the structure of Tanya! I want to know what each perek DOES and how it brings us to the next perek. What chapters are thematically grouped and why does one group come before the next? I am going to make a MAP of Tanya." So, I sat down and started working feverishly. I read everything I could get my hands on that would explain the flow and structure of Tanya. Of course, there was the Tzemach Tzedek's Kitzur of Tanya but I also read everything else I could find. I would comb through Shiurim B'Sefer HaTanya looking for the little introductions at the beginnings of the chapters that would explain how we got to this chapter from the last chapter. Also, particularly helpful was Nissan Mindel's introduction to the English translation of Tanya. There, he lays it all out as far as the structure of the book.

Anyway, I worked on this "map" of Tanya, which was really just my handwritten notes which I later typed up on the computer. I was finished by Chof-Daled Teves, the Alter Rebbe's yahrzeit which was five weeks from the time that I had started. I didn't sleep much during that time.

Well, eventually the map was published by Kehos. I had to re-edit it a little bit and of course, all of the graphic design elements needed to be constructed, but basically, the whole map was done between Yud-Tes Kislev and Chof-Daled Teives, 5763 (the winter of 2003). I also had to make one major structural change in the map which was based on a comment by R' Yoel Kahan. The way I had the map was that 33 and 34 begin the theme of Moshiach which is continued until 37. R' Yoel said that 33 and 34 are a continuation of the PREVIOUS group of chapters, 26-31, which speak about joy. The fact that chapter 32 interrupts the flow is precisely that, an interruption, added later by the Alter Rebbe, but the theme begun in 26 really continues until 34.

A couple of years ago, the JLI (Jewish Learning Institute) asked me if I could turn the map into the basis for a curriculum on Tanya. Of course, I was very excited to take on the project. The way I devised the course was to really try to bring out that although we cannot possible do justice to Tanya in 6 weeks, we CAN give you a feel for its structure in that amount of time. Each week, the course presents another phase of development. There's a certain closure at the end of each lesson where the person feels, "Now I've got it." Then, they go out and try to live perfectly with that information alone and they hit a wall. The come back next week desperate for another meeting with the Alter Rebbe because they need the next piece of advice to get them through the next phase. It's really neat watching students go through the steps of Tanya like that. And the most important thing is that they achieve this growth by going through the Tanya IN ORDER. I think that sometimes, we do a disservice to our students when we present them with "themes" in Tanya. We try to pick out all the chapters from all over Tanya that mention one concept and then put them all together and teach them. That's like playing a symphony for someone by first playing them all of the F's and then all of the E's and so on.

Just the other day, someone told me that 14,000 students all over the world are currently taking the JLI course on Tanya and that this is the biggest course in Tanya ever. It's really exciting to think of all these thousands of Jews who are going to have tasted what it's like to really live with the Tanya. I'm fully expecting an all out revolution to come from this.

Now, I'll try to answer your second question.

How do you feel that your understanding has developed since the first time you picked up this sefer?

The more I learn Tanya, the more I discover about it that I completely don't understand. The Rebbe Rashab said that our understanding of Tanya is like a goat looking at the moon. All I can say is that, they very little bit of Tanya that I do understand (or that I think I understand) has changed my life and helped me to give other people the tools to change their lives as well.

Ahavas Yisrael & Yiras Shamayim

If a person does not feel more Ahavas Yisroel after learning and davening, this is a sign that he does not have yiras shamayim.

(Divrei Yisroel)

Tuesday, December 02, 2008

Naivete & Tzedaka

"Mark" and "Uncle Dave" came over to the more affluent section of town each afternoon with the hopes that kind-hearted college students would be sympathetic and give them a dollar here or there. As a somewhat naive college freshman who had never lived in a big city, I was somewhat intrigued by their humor and easy going nature. I don't exactly remember the details of how it all started now, however, I spent countless nights that first semester sitting out in front of the record store with these two African-American homeless men keeping them company as they begged for spare change.

Aside from all the jokes we would tell, there were times when they told me about things they witnessed the previous night in the crime-ridden section of the city, or things that had happened in the abandoned building where they and many crack addicts would sleep at night. Now as I am writing this, I recall that there was even one time when Mark and I took the subway over to his neighborhood to go to a movie there together. After buying him some fried chicken for dinner later that night, I remember walking past the crack addicts before I got back on the subway and returned to the safety and security of my college campus.

Our friendship became strained as the months went on. There were times when he called my dorm room in the middle of the night and asked me take money out of the ATM for him because he was in trouble. Although I agreed and went and got him $20 from the ATM on one or two occasions, on other occasions I lied and told him that I did not have any money because I felt that I was being used. I felt guilty afterwards, nevertheless, I started taking alternate routes so I would not need to go by the record store and could avoid him.

I returned to campus the following year school year and I noticed that only "Uncle Dave" was still out in front of the record store; still attempting to dance like James Brown while singing a medley of R&B songs. When I asked him were Mark was, he replied that Mark was sent to prison over the summer for armed robbery. (Ironically, Mark had always said he was the clean one and candidly told me that Uncle Dave was a heroin addict.)

Reflecting upon that time in my life, I can now see that that my understanding of the concept of tzedaka displayed a certain element of naivete. Tzedakah is ultimately about the giver and not the receiver, however, if we don't investigate whether the people we give tzedaka to are truly worthy, then are tzedaka may not truly be tzedaka.

5 Kislev Links - ה כסלו

Teitelbaum Orphan Fund: Emergency Appeal

Kruman Foundation: Emergency Appeal

ChabadIndia.org: Chabad of Mumbai Relief Fund

Treppenwitz: Please don't call it 'Hashgachat Pratit'

Rabbi Tal Zwecker: Degel Machaneh Ephraim - Parshas Vayeitze

Treppenwitz: A tale of two engineers

Shturem.net: The Sefer Torah from Mumbai

A Language That He Does Not Understand

Evil is not essentially evil but a good we cannot see. Although certain events may appear to be evil, this does not express their essential character but only reflects our insufficient understanding. This can be compared to one who is being addressed lovingly but in a language that he does not understand. No matter how many affectionate words are spoken to him, he may experience anger, frustration, the feeling that he is wasting his time, and so forth. Similarly, because we are incapable of understanding, certain levels of goodness that G-d draws down to us appear as imperfect and evil.

(Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz)

Monday, December 01, 2008

Question & Answer With Rabbi Micha Golshevsky - Sharing The Same Name

A Simple Jew asks:

Rebbe Nachman of Breslov said, "Do not wonder how a name can contain the secret of a person's existence when so many share the same name. It is an error to question this."

I certainly would never consider questioning the validity of this teaching from Rebbe Nachman. I would, however, like to understand it better. Could you elaborate a bit further on this general topic and the issue Rebbe Nachman raised in particular?

Rabbi Micha Golshevsky answers:

First of all, the Ramaz writes that ones' name is his neshamah.

Chazal tell us that when Hashem told the angels to give names to the animals they could not, but when Adam received this task he immediately assigned names to them all.

The Chidah asks the obvious question: why couldn't the angels name the animals?

He explains: one's name contains his mission and ability to choose good or bad. This explains why Chazal sometimes teach a person's good or bad deeds from his name.

We can extrapolate a little of what this means from the Zohar Hakadosh which teaches that the letters of the holy Torah are from the loftiest spheres and emanate from the Boundless Light of Hashem as it were. We cannot fathom even a fraction of the greatness of even one letter of Torah or tefilah.

But what does this really mean?

Rav Ya'akov Abuchatzeira compares the letters of the Torah to a body and soul. Just as one's soul can only interact with the material world through the physical vehicle of his body, the boundless Supernal lights imbued in the letters of Torah can only be accessed in this world through the physical forms of the letters of the Hebrew alphabet. It is only through these forms that these illuminations interact with our physical world.

Just as even twins may have a very different spiritual nature (like Ya'akov and Eisav for example.) the same letter can sometimes access different spheres of the supernal light it reveals. Even identical twins can take very different paths in life. One may be spiritually upwardly mobile while the other may be in a very low spiritual slump.

So there is your answer: Each letter of our name represents a lot of potential — for good or for bad. What we do with it is up to us.

I was once interviewed by a fairly prominent Talmud Chacham, also a great mekubal, for entry into his kollel. While I was speaking with him, a clean shaven young man with furrowed brow, (presumably his son) approached.

"What's on your mind?" the Rosh Kollel asked.

"What in the world is behind the custom of saying a pasuk the first letters of which make up one's name before yihiyu liratzon in shemonah esrei?"

The Rosh Kollel mentioned an earlier source for this custom but the young man was obviously not satisfied. "Yes, but why does this practice enable one to 'remember' his name after he dies? And, why does remembering his name make his judgment any easier, for that matter?"

The elderly man shrugged. He clearly had no idea.

Although I knew nothing about kabbalah and was not in this erudite scholar's league, I knew the answer to his sons question. You see, I had learned through a little sefer called Meshivas Nefesh which explains this issue in great depth.

Rav Nosson writes there that one's name refers to his potential for good. One who "forgets his name" is a person who has forgotten his potential for good in the world. One who "remembers his name" knows that Hashem takes pride in every Jew as long as he feels proud to be a Jew, no matter what his spiritual level (as Rebbe Nachman writes.)

This is the meaning of a dead man "forgetting his name." He is so disconnected from the good within that he doesn't connect to it. He cannot yet access the good that he has done, although this is his true essence.

One who reminds himself of his name at frequent intervals can easily return to Hashem since he is proud of his intrinsic connection with Hashem as one of the chosen nation.

Now we can understand why we recite a verse at the end of each shemonah esrei before yehiyu liratzon. Mentioning a verse in Tanach which alludes to our name and our mission in this world, we recall that every Jewish soul is rooted in the boundless lights symbolized by each and every letter of the Torah.

Hashem should help us always truly recall our name and reconnect to our intrinsic worth. Let us remember that we are important and beloved to our Heavenly Father; no matter what!

Deriving Benefit

One should not seek the light of a tzaddik for material benefit, as is common in our generation. Rather, one should attach oneself to the tzaddikim for spiritual purposes only.

(Reb Nosson of Breslov)

Sunday, November 30, 2008

Likutey Moharan - Volume 12 Now Available

Breslov Research Institute has just released Volume 12 of the English translation of Likutey Moharan. This volume begins Part II of Rebbe Nachman of Breslov's magnum opus and contains lessons 1 through 6.

Chanuka Special: Buy a set of all 12 volumes of Likutey Moharan for the price of 10 and get free shipping on this item. Please use code LM12 when ordering.

Friday, November 28, 2008

Ribbono Shel Olam!

Ribbono shel Olam! When a Jew drops his tefillin he is shocked and distressed. He lifts them up from the floor, kisses them with reverence, and fasts the entire day to atone for their humiliation. Ribbono shel Olam! Your tefillin, the Jewish people - for two thousand years they are lying downtrodden on the ground. When will you raise them up? When, when will you raise them up?

(Rebbe Levi Yitzchok of Berditchev)

Question & Answer With Akiva Of Mystical Paths - Emuna & Eretz Yisroel

A Simple Jew asks:

Looking back since the time you made aliya, do you think that your emuna while living in the United States was lacking? How is your emuna living in Eretz Yisroel stronger today?

Akiva of Mystical Paths answers:

When I was a child, my grandparents used to take me on outings to the Franklin Institute - possibly _the_ original children's science museum (located in Philadelphia). At the time, the museum was the ultimate hands on science museum. They actually had full size steam locomotives in the building that you could climb on and partially operate. They had a full size commercial jet you could climb through, and in the cockpit things were wired to light up. Small hands on experiments abounded - pull and lift tons of material with ropes and pulleys, experiment with wing lift in miniature wind tunnels, make huge sparks and pull and push with electromagnets. And when they did demonstration experiments, they were exciting, noisy, messy, and flashy.

The wonders of science were literally in your hand, and that sparked my interest and imagination for a lifetime. Turning on a light is not abstract when you've had a chance to experiment with it.

Judaism is a religion, a way of life, a people, a nation, and a land. These things aren't separate, together they make up a complete package.

Outside of Israel, much of Judaism is theoretical. Parts don't apply and are only studied in abstract (shmittah, trumah). Parts are performed but don't align (prayers for rain are seasonal by schedule in Israel). And parts are hard to understand or relate to (aliyat haregel).

Judaism in the Land of Israel is a hands on experience like the science museum memories of my childhood. While we went down the road to Bet Lechem to Kever Rochel, my 8 year old daughter looked up at me and quoted from the Torah, asking "is this the road she was buried on", yes it was, the words of the Torah where we stood. When we went to Ir Dovid (excavations of the ancient city of King David on the far side of the Old City, next hill over), we went down through the water tunnel (30 minutes in the dark with water up to your ankles) that ends with a plaque saying "we are the workers of King Chizkiyahu, we dug from both sides to prepare for a siege by the Assyrians" (they really found the plaque there, though it's a reproduction there now with the original in a museum) - the words of Melachim in front of our faces.

We discussed shemittah in the market on which vegetables we could buy (or not) and the empty fields we passed. Trumah and maaseros will be taught in the kitchen as we take them.

Myriad generations of our patriarchs and matriarchs, tzaddikim and gedolim can be visited at their kevorim. Learning mishnah, Rabbi Akiva says - been there. Zohar, Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai says - been there. Mishneh Torah, the Rambam says - been there. Shulchar Aruch or Kabbalah, Rabbi Yosef Karo and the Ari, yep. Shimon HaTzadik, Shmuel HaNavi, Binyomin, Dan, Shimon, so many more. Jump in the Ari's mikvah, climb down to the cave of Eliyahu HaNavi. Stand in Elon Moreh when the parshat hashavuah says Avraham Avinu came there, look over to Har Bracha and Har Gerazim where Am Yisroel stood upon entering the Land.

There's a story from the Kedushas Levi, Rebbe Levi Yitzchok of Berdichev. When he was newly married, he heard of the Maggid of Mezerich and insisted on traveling to learn by him. Upon returning, his father-in-law challenged whether he was wasting his time or not..."What did you learn by the Maggid?" asked his father-in-law. "That there is a G-d." replied the Kedushas Levi. His father-in-law called over the maid and asked her "do you know that there is a G-d?" "Yes" she replied. Said the Kedushas Levi, "she says there is a G-d, now I _know_ there is a G-d."

In America, I read and learned and prayed, and went to work. While I spent time learning chassidus, I didn't spend all that much time contemplating G-d, thinking about the avos and imahos, navi'im and kesuvim. Intellectually I strove to become closer to Hashem, but "sheviti Hashem l'negdi tamid" - keeping Hashem constantly before me or in my thoughts wasn't part of the program. My home felt basically secure, my parnossa basically secure (though that's changed in the US recently, and many of my former colleagues have lost their jobs within the last month), and one could contemplate which tzedakah is more worthy for my giving.

In Israel, much of Judaism is literally within reach or within sight. Parnossa is challenging, I thank Hashem every day for just getting by. Holy sites from generations are nearby, to light up a moment. Life and death threats are more palpable, both from brutal enemies and even from normal traffic. And I encounter our neighborhood poor who literally survive by communal chesed or (G-d forbid) go hungry when it's lacking.

In other words, emunah is more hands on, more literal and in your face. In the US, the gedolim and tzaddikim certainly know that every moment we depend on Hashem. In Israel, not only does every religious Jew know that but even many of the non-religious admit it as well.

In Israel, we live by the hand of Hashem every day.

Unanswered Questions

One can ask questions - all kinds of questions - without those questions undermining one's faith. I was once a student of mathematics. I know about so many unanswered problems and so many paradoxes and so many logical contradictions. Do these things undermine my belief or understanding of mathematics? Not at all.

(Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz)

Thursday, November 27, 2008

Guest Posting By Rabbi Ozer Bergman - Alarmists

For better or worse, I am not an alarmist. So when I got an e-mail or two that tzaddikim of various stripes were warning "The End is Near for American Jews! Get Out While You Can!" I was a little underwhelmed. After all, I've gotten e-mails in the past that "Mashiach is DEFINITELY coming by this coming Rosh HaShanah" and, sadly, he didn't. In other words, the track record of alarmists is not an argument to heed any of their warnings.

Mind you, I don't mean to say that their messages should be ignored or summarily dismissed. Rather that current events are fairly inscrutable and people should not hurriedly make life decisions based on what's reported in the e-mail de jour that so-and-so said such-and-such. Did he? Exactly what did he say? In what context? Was he addressing his own congregation/community/adherents or all of Klal Yisrael?

Nonetheless, even Ozer Laidback realizes that what we're witnessing requires a response. The world is certainly undergoing some serious changes, even if those changes aren't leading immediately and directly to Armageddon (you'll pardon the expression). Some of us are old enough to remember the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of Communism. Maybe now it's time for capitalism and democracy to fall. After all, despite any personal affinity we may have for them, neither is kadosh or Torah m'Sinai.

That said, please allow me a digression. I want to publicly express my dismay and distress about the reaction of too many people. The reaction and my subsequent distress go back to 9/11. Too many (even one is too many) in our community feel that gloating is an appropriate reaction to America's trials and tribulations, to its suffering and setbacks. This is an un-Torah and even anti-Torah attitude and view.

Our holy Torah teaches us that converts from certain nations, though they become Jewish, may never marry into what is called Kahal Hashem. Some may marry in after a defined waiting period (Devarim 23:4-9). Egyptian converts may marry after three generations because we we were guests in their land. Even though they enslaved, humiliated and beat us for close to a century; even though they drowned millions of Jewish babies, because they gave us a place to stay when we were in need we are not to totally shun them (see Rashi, v.8).

In Sefer HaMidot (aka The Aleph-Bet Book) Rebbe Nachman teaches that it is forbidden to be an ingrate, to a Jew or to a non-Jew (Tefilah A:62). This seems to be based on "David asked, 'Is there still anyone left of the House of Shaul with whom I can do kindness for the sake of Yonatan?'" (2 Samuel 9:1); and on "David said, 'I will do kindness with Chanun son of Nachash, as his father did for me...'" (ibid. 10:2). The Rebbe also teaches that one is obligated to pray on behalf of his host city (Tefilah A:56).This is apparently based on Yirmiyahu HaNavi words, "Seek the peace of the city to which I have exiled you. Pray to God on its behalf because its peace will be your peace" (Jeremiah 29:7).

Whatever the shortcomings and failures of the United States of America in regards to its Jews and the Jewish people, it has been a very, very good home to millions and millions of us. Instead of gloating, we ought to be praying strongly for its protection and prosperity. Amen.

Returning to our initial topic: Mashiach has to come; why not sooner than later? God is shaking things up, and that is certainly part of the unfolding process that will result in Mashiach's arrival—speedily, in our lifetimes. Amen! But in the meantime it is both disconcerting and scary. What can we do get our bearings and overcome our fears of the what the future holds?

Rebbe Nachman recommends holding on to a genuine tzaddik. The Torah teaches that in the Messianic era Hashem will grasp the ends of the earth and shake off the wicked (Job 38:13). But the genuine tzaddik—and those holding onto him—will not be cast off. He/they will survive. Let's work on strengthening our faith in Hashem's unending, loving providence (aka hashgacha pratis), that on the heels of this cloudy whirlwind ride, is clarity and calm. Let's actively seek out the clear wisdom and advice of genuine tzaddikim, past and present, and do our best to live accordingly. Amen.

Our Inner Self

One should not speak one thing outwardly and think otherwise in his heart. Rather, his inner self should be like the self he shows to the world. What he feels in his heart should be the same as the words on his lips.

(Rambam)

Wednesday, November 26, 2008

Vanished

The Sudilkover Rebbe told me recently that he had some bad news to share with me. The laptop computer he was using to work on his new edition of Degel Machaneh Ephraim was severely damaged and computer specialists could not restore the contents of his hard drive. This hard drive contained the only copy of his commentaries on the Vayikra and Likkutim sections.

Countless hours and of months of work vanished.

When his son asked him why he thought it happened, the Rebbe responded that perhaps he not have the right machshavos (thoughts) when working on it. He had done much of the work on these lost sections following the death of his father. The Rebbe explained to his son that it was also possible that he did not work with the proper simcha that was necessary when working on a sefer as holy as Degel Machaneh Ephraim.

Instead of becoming frustrated and irate about this unfortunate occurrence, the Rebbe accepted it with simple emunah. His reaction thus became an important life lesson to me; don't rush to cast blame on something external when more the likely the problem was created by a deficiency that was internal.

28 Cheshvan Links - כח חשון

Dixie Yid: Our Friend's Child Needs Help

Modern Uberdox: Revealing contents

Alice Jonsson: Descending From the Throne

A Simple Jew: A Day To

Eizer L'Shabbos: Winter Campaign

Humility

A person should never let his own smallness insignificance and humility cover up his true greatness. For sometimes a person downgrades himself to excess and forgets that he still has many amazing attributes.

(Rebbe Nachman of Breslov)

Tuesday, November 25, 2008

Question & Answer With Rabbi Tanchum Burton - Advice & Initiative

A Simple Jew asks:

In Rabbi Chaim Kramer's book, "Through Fire and Water" he wrote, "It is up to the individual to take the initiative and act on the Rebbe's advice. The Rebbe's lessons are universal, speaking to each individual on his own level in accordance with his unique mission in life."

Additionally, he observed, "What is striking about his teachings is that, while the tzaddik is undoubtedly the central figure, he rarely intervenes as such in the lives of his followers. Rather, he observes and - most important - advises, sometimes with as little as a nod, a gesture, or even silence."

Is this "hands off" approach to leadership unique to Breslov or are you aware of any other Chassidic groups which are predominantly guided by the self-motivation of the chassidim?

Rabbi Tanchum Burton answers:

It seems to me that Rabbi Kramer was utilizing a rather poetic device to describe the experience one has when learning the works of Rebbe Nachman.

In Likutei Halachos, Shluchin 5, Reb Noson indicates that we do not need the Tzaddik for his arms and legs, but rather for his teachings. What he seems to have indicated is that the whole experiential aspect of having a rebbe - the grandeur of the court, the slices of fruit passed from hand to hand at the rebbe's tisch, the rebbe's royal appearance - is not as important as the avodas Hashem that results from the successful learning and integration of that rebbe's teachings. The litmus test of a rebbe-chassid relationship is whether or not the quality of the chassid's faith and service of G-d through Torah and mitzvos has increased by virtue of his encounter with the rebbe.

The Rebbe said that he wanted us to be gebakeneh chassidim, literally, "baked through and through". What he meant was that our integration of his teachings should be so thorough that every aspect of our avodas Hashem should reflect these teachings. That does not mean that we have to follow a particular chassidische dress code, or eat specific types of Jewish foods (although the Rebbe was clear that a Jewish appearance, e.g. a beard and payos, was important, see Chayei Moharan). What it does mean is that, given that his writings are replete with advice on how to serve G-d, we ought to turn to those writings, as they contain everything we need to live and grow as Jews. Thus, the teachings are the most important aspect of the Rebbe.

Breslov has a very unique tradition in this manner. Amongst the Breslover chassidim have been many people who could easily have become chassidic rebbes in their own right, having distinguished themselves as Torah scholars, dayyanim, miracle workers, and intense ovdei Hashem. Nevertheless, these people chose to remain talmidim of Rebbe Nachman. The Rebbe himself was very different from his contemporaries. Most of the time, when we read about the "chassidic masters", we find descriptions of spiritual superstars and their accomplishments, and of the size of their large followings - but rarely do we read about talmidim who have attained high levels. With Rebbe Nachman, although we have a litany of accounts that aptly convey a sense of his stature as a rebbe and tzaddik, the most important mesora we have from him is his advice on how WE can become spiritual superstars. It is this coaching role that the Rebbe plays in our lives that I feel distinguishes Breslov from other traditions.

The Rebbe physically left this world in 1810, but remains with us through the daas he bequeathed to us, and through the mesora that his talmidim in each generation have passed down to us. Since the Rebbe's teachings are the main vehicle by which one, through learning and integrating them, forges his relationship to him, it is up to the individual to take the initiative. That may explain what appears to be a "hands-off" approach in Breslov. But I can assure you that with the right teachers and good friends, when you get caught in the Rebbe's "net", the desire to live these eitzos make them no less than standing orders. May Hashem help us merit this.

27 Cheshvan Links - כז חשון

Breslev Israel: Boss Blues

A Fire Burns in Breslov: Admitting an Error

Modern Uberdox: Opening My Heart

A Simple Jew: Esav's Questionable Shechita

Rabbi Dovid Sears: A Biblical Generation Gap

Dixie Yid: The Freedom of Shabbos Restrictions

A Simple Jew: וַיֵּצֵא הָרִאשׁוֹן אַדְמוֹנִי

Circus Tent: All by the book, None by the heart

Neither Ethical Nor Healthy

The obligation to judge favorably is incumbent on every Jew - man or woman - at all times, and in respect to every Jew - man, woman, child, or adult. Although there is no Torah commandment not to suspect a non-Jew, nevertheless, it is neither ethical nor healthy to be suspicious of anyone, and it can cause a breakdown of one's fine character traits. One should strive constantly to maintain peaceful relations with everyone and to live in harmony with all.

(Mishpetei Hashalom)

Monday, November 24, 2008

Guest Posting By Chabakuk Elisha - A Layman's Perspective On Turkey And The Halachic Process

With Thanksgiving on the horizon (for Americans like me) we see quite a bit of Turkey promotion. Of course, most people know that Turkey was not served at that first thanksgiving meal, but being that the Turkey is of American origin, it is "rewarded" with its 24 hours of fame. However, the Turkey's American origin raises Halachic questions as to its Kashrus status, and all you could want to know about the topic can be found here. But, skipping ahead, the bottom line is that Turkey is accepted as Kosher. And the reason? Well, basically, because people were already eating it. The questions raised are post-facto: "Why is Turkey Kosher?" and not "Is Turkey Kosher?"

When I was younger this troubled me. Not only this, but even that there could be different opinions about the status of something according to Torah: How could G-d want us to do the right thing, and then leave it ambiguous? How could He leave everything to fallible humans to figure out and determine, and have them come out with different answers? Different customs I could understand, but differences Halacha? Shouldn't there be one single right and wrong answer? Isn't there a right or wrong answer?

Of course, the question is the answer, but it's still worth discussing. And it's a common problem that I run into: people will say, "If it's Halachically permitted, then we can do it without a second thought – regardless of what people do," or they'll debate if something should be done differently or allowed/disallowed because of XYZ. That's all fine and good from an academic POV, but it's not the way it works. There is a Halachic process, and Klal Yisroel, in fact, plays a very big role in determining the halacha. Halacha is not a cold canonized list in Heaven of Do's and Don'ts; it's just not that way. Halacha is far more complicated; it's a combination of a number of things, and among them is intuition as well as the process of acceptance by observant Jews – and this is a significant element to the underlying difference between what we call Rabbinic Judaism and such strains as the Tzadokim or Karaim (Sadducees or Karaites). Rabbinic Judaism is centered on the rule that "Torah is not in the Heavens" while Tzadokim /Karaim refuse to accept that there can be different answers to the same question al-pi Torah.*

In fact, "Halacha," as we call it, has its own rules and its own reality. For example, Halachic principles such as probability and nullification or how things are defined don't have to match other information that we call "facts." And with us all living in an era that places so much weight on scientific data, it is easy to try to define things in similar terms, but it's not really a good fit and while there is some overlap, they'll never really be aligned. In fact, religion in general is more of a philosophy than a science, and the same is true here:

Perhaps we could compare Halacha in a certain way to a vow. If, let's say, I vowed not to eat chickens, they would become forbidden to me. Similarly, the Halachic process determines the rules. So, along comes the Turkey. It is quite possible, maybe even likely, that it wouldn't have been accepted as Kosher if we analyzed it today from scratch – but that's not the way Yiddishkeit works. Instead, Klal Yisroel paskened, and it is Kosher. Virtually all authorities explain how it is kosher; the actual psak is basically a fait accompli. So, to me, the Turkey represents the power of Klal Yisroel in Halacha. It represents the process. To me, it represents a significant element in the system of Yiddishkeit.

* Of course, there is much more to the battles of the Tzadokim / Karaim vs. Rabbinic Judaism, but it isn't relevant to this piece.

26 Cheshvan Links - כו חשון

Mystical Paths: The End of The Chassidic Movement

Chabakuk Elisha: Honesty

The Sofer: Power of a Mitzva

A Simple Jew: "The Masses Preferred Esav"

Redigging The Well

Each person only receives in accordance with his yearning, his desire and effort, i.e. how much he pushes and digs with the words of his mouth and with his heart to find the water within the holy wells - the wells of fresh, living water that were dug in the days of Avraham and which the Philistines stopped up and filled in with dirt. Afterwards Yitzchok Avinu came back and redug them. He had many fights and arguments over them, because those who opposed him, then called the Philistines, quarreled with him a great deal. He finally dug and found the well of fresh, living water and named it Rechovot. Yet these wells are still stopped up, and since that time the tzaddikim and prophets of every generation have struggled enormously to dig them out and reveal them.

(Reb Nosson of Breslov)

Friday, November 21, 2008

Guest Posting By Rabbi Dovid Sears - Chasidic Mysticism Today - Part 2

Continued from Part 1:

Perhaps the first attempt to create a specific technique not reserved for a spiritual elite was the approach to the daily prayer service conceived by Rabbi Aharon HaKohen of Zelichov. His commentary on the siddur, Kesser Nehora, attempts to summarize the kavanos of the Ari z"l in a way that addresses both the mind and heart. He defines the parameters of "the service of the heart" according to four basic themes: awe of G-d, love of G-d, praise of G-d, and the acceptance of G-d's Kingship (Malkhus). These four categories correspond to the four letters of the essential Divine Name (Y-H-V-H). By praying in the manner he prescribes, one fulfills the Psalmist's words, "I have placed G-d before me always." First published in 1794 together with the Siddur Tefillah Yesharah (his own redaction of the formal prayers according to the Chasidic custom, also known as the "Berditchover Siddur"), Rabbi Aharon's system of kavanos is still used by many Chasidim today.

One of the most profound thinkers to develop the Baal Shem Tov's teachings was Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi (1745-1812). His highly intellectual approach came to be known as Chabad Chasidism, borrowing the Kabbalistic acronym for the three sefiros of Chochmah (wisdom), Binah (understanding), and Daas (knowledge). Born of the dispassionate Lithuanian temperament, Chabad distrusted the fervor of many Chasidim as a "delusion of the blood," the self-serving pursuit of an emotional high. Alternately it developed a philosophical-contemplative method by which the seeker might spontaneously experience an intuitive sense of his own nothingness (bittul ha-yesh) and the omnipresence of the Divine. This emotional consequences of such contemplation would be a natural by-product of the quest for unity. In this way, Chabad sought to kindle a steady inner flame in the heart, rather than fan the fires of sporadic -- and possibly false -- ecstasy. The basic practice, still employed by some contemporary devotees of Chabad, entails intensely and systematically contemplating the kabbalistic order of the universe. This is known as the Seder HaHishtalshelus, or "Chain of Being," and the exploration of its intricacies produced a profound literature and a unique spiritual path. The core of these teachings may be found in Rabbi Schneur Zalman's famous Sefer HaTanya, especially in the second section, Sha'ar HaYichud V'HaEmunah. Other key works include Ner Mitzvah V'Torah Ohr and Kuntres HaHispa'alus by Rabbi Sholom Dov Ber of Lubavitch. However, virtually all Chabad texts work out the implications of Rabbi Schneur Zalman's ideas in various contexts.

More suspicious of the rational faculty than the founder of Chabad, Rabbi Nachman of Breslov (1772-1810) wanted the individual to attain a realization of G-dliness through the fabric of life itself. He stressed the path of hisbodedus -- secluded self-examination and spontaneous personal prayer. One sets aside one hour every day to pour out his heart to G-d, preferably in a secluded place in the middle of the night. Rabbi Nachman encouraged the seeker to overcome his worldly attachments by stripping away one level after another of the "false self" until all that remains is the subtlest trace of ego -- and then one may let go of this, too, permitting the Infinite Light to shine through at last. This process necessitates reflecting upon one's life circumstances and experiences, especially by using the Torah one has studied (and Rabbi Nachman's discourses in particular) as a springboard for meditation and prayer. A general description of hisbodedus is given in Likutey Moharan 1, 52, and II, 25, as well as in the anthology Hishtapchus HaNefesh (translated into English as "Outpouring of the Soul" by Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan). But actually, the possibilities of hisbodedus are unlimited -- for according to Rabbi Nachman, every aspect of the human condition can be a starting point in one's search for G-d.

Like all Chassidic masters, Rabbi Zvi Hirsch (Eichenstein) of Ziditchov (1765-1831) and his nephew and disciple, Rabbi Yitzchak Isaac Yehudah Yechiel (Safrin) of Komarno (1806-1874), saw the teachings of the Ari z"l and those of the Baal Shem Tov as part of both an essential and historical continuity, an ongoing revelation of the deepest levels of Torah. On this basis, they felt justified in more openly discussing the mysteries of Lurianic Kabbalah, even delving into the use of kavanos and yichudim, meditations upon various Divine Names. When performed by a worthy individual in a state of purity and with holy intent, these meditations restore spiritual harmony to the universe and elicit Divine mercy and favor. (However, as the Rebbes of Ziditchov and Komarna also warned, when kavanos and yichudim are employed indiscriminately, the results may be catastrophic.) Perhaps the best introduction to this path is Rabbi Yitzchak Isaac Yechiel's Netziv Mitzvosecha. His diary of dreams and visions, Megillas Sesarim, is one of the most revealing personal testimonies written by a Chasidic master. (In a similar vein,some of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov's dreams and visions may be found in Chayei Moharan, translated by Avraham Greenbaum and published in English as "Tzaddik". The dream-journal of another major Chasidic thinker, Rabbi Tzadok HaKohen of Lublin, was published as Kuntres Divrei Chalomos.)

Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman (Shapira) of Piaseczno (1889-1943), a more recent Chasidic leader who perished in the Warsaw Ghetto, brought an illumination of mysticism to the masses through his innovative educational methods. By imbuing the student (or disciple) with a deep sense of his own essential nature, the Piaseczno Rebbe initiates him into Torah study, prayer, and the performance of mitzvos by using visualization techniques. These improvisational kavanos are sometimes derived from the Kabbalah, but avoid its more esoteric aspects. The Piaseczno Rebbe's ultimate goal is not only to bring the everyday practices of Judaism to life but to initiate his disciples into the ethereal realms of the spirit. His best-known works are Chovos Talmidim (translated to English as "A Student's Obligation" by Micha Odenheimer) and Hachsharas Avreichim. But perhaps the clearest exposition of his approach may be found in a small booklet entitled Bnei Machshavah Tovah. These works began attaining popularity during the author's lifetime and have more recently inspired a growing number of devotees in Chasidic yeshivos, especially in Israel.

However, like everything else in Torah, one can learn only so much from texts. Even since the Torah was given at Mount Sinai, the tradition has been passed down from master to disciple, and especially in this inner dimension of Torah, one must find a teacher. Some Chasidim would argue that this master-disciple relationship is even more important than the particular school to which one belongs.

The Gemara tells us to search for a teacher who is comparable to a "malach Hashem Tz'vaos," "an angel of the Lord of Hosts". The question is: where can one find such a teacher? And how can one know if he is making the right choice? The answer I received from my teachers is that you have to be willing to search as long as it takes -- and, like everything else (and maybe more than everything else), you have to pray for Divine assistance.

Pray For Rain!

Received via e-mail from Rabbi Ozer Bergman:

On my way to Meron this past Monday (of Parshas Chayei Sarah), I passed through Tiverya (Tiberias).

GEVALT!

The Kinneret (Sea of Galilee) is shrinking, shrinking, shrinking. What was once part of the seabed is now coast! Wide patches of the lake are BROWN.

That there has been less than sufficient rainfall here in Eretz Yisrael for the last few years, is not news, at least for those of us who live here. But seeing how bad it is, was a clear sign to me that it can chas v'chalilah get worse.

I am not a poseik, but I think we can start saying extra Tehilim and mishebeirakhs (is that a word?), even on Shabbos, that Eretz Yisrael be blessed very soon with gishmei berakhah. Even though it's a tad early for this year's late-in-coming rain, it's not too early for the accumulated dryness from which we're suffering.

May Hashem bless us to soon praise His Name and to be dancing in the rain of gishmei berakhah. Amen.

On my way to Meron this past Monday (of Parshas Chayei Sarah), I passed through Tiverya (Tiberias).

GEVALT!

The Kinneret (Sea of Galilee) is shrinking, shrinking, shrinking. What was once part of the seabed is now coast! Wide patches of the lake are BROWN.

That there has been less than sufficient rainfall here in Eretz Yisrael for the last few years, is not news, at least for those of us who live here. But seeing how bad it is, was a clear sign to me that it can chas v'chalilah get worse.

I am not a poseik, but I think we can start saying extra Tehilim and mishebeirakhs (is that a word?), even on Shabbos, that Eretz Yisrael be blessed very soon with gishmei berakhah. Even though it's a tad early for this year's late-in-coming rain, it's not too early for the accumulated dryness from which we're suffering.

May Hashem bless us to soon praise His Name and to be dancing in the rain of gishmei berakhah. Amen.

A Previous Incarnation

I heard that a man is guilty of sins he had committed in a previous incarnation. But when he prays on behalf of sinners, his sins, too, are put right.

(Degel Machaneh Ephraim)

Thursday, November 20, 2008

Guest Posting By Rabbi Dovid Sears - Chasidic Mysticism Today - Part I

Orginally included as an appendix to "The Path of the Baal Shem Tov" (Jason Aronson 1997), a collection of early Chasidic teachings on various topics, this essay has been revised by the author for this blog.

The teachings of Chasidism have both strengthened and transformed Jewish spirituality. Perhaps the Baal Shem Tov's greatest success was in promoting his values: joy in the performance of mitzvos, love of

G-d as the greatest incentive for ethical behavior, an appreciation of the inestimable worth of the simplest Jew and the smallest good deed, and attachment to tzaddikim as the key to spiritual survival and growth. Not only is the master's influence still felt in the Chasidic world, but, in one way or another, there is almost no sector of Klal Yisroel it has not affected.

But as the quest for deveykus, mystical cleaving to God, there is hardly a yeshiva, even among the Chasidim, where the subject is mentioned. Yet this was probably the Baal Shem Tov's central concern. What happened?